Acaté Celebrates 10 Years – A Retrospective

2023 marks the ten-year anniversary of Acaté. The genesis of our organization did not begin with the launch of our website in 2013, but we would like to commemorate this milestone by reflecting on our work over the past decade and present our vision for the future of the organization.

When our team members talk about our work, people are often curious about how our organization came together and ask us how we started a non-profit that works with the Matsés. Our field reports and public messaging over the past ten years have focused wholly on the projects but we thought it would be nice on this special occasion to share the founding story of our organization.

The Early Beginnings

Acaté Co-Founder William Park (Bill)

In 2003, I set off with a friend and two guides on an overland trek to the remote Peru-Brazil border area. Growing up in New York I had always wondered what a true wilderness area was like (at the time I did not understand that many of these areas are indigenous territories). The area from the Ucayali River in Peru and extending east well into Brazil seemed to be the largest wilderness area outside of the far north. The plan was to cross over the western part of this area and then float back on rafts to the Ucayali. In my military days I had marched for over 20 miles in a day with a heavy pack, so a 100-mile trek with guides seemed achievable. The terrain became exceptionally challenging after the first 15 miles on an open trail. The area consists of hills separated by streams and palm swamps with deep sucking mud. There were frequent logs to climb over, some chest high, and the slippery clay soil made going up and down the hills difficult. Crossing the ubiquitous palm swamps and streams was very slow as a misstep would mean sinking into the mud, sometimes almost waist deep. The streams are in steeply banked ravines that must be crossed by tightrope walking over a small log. After five days of walking in the extreme heat and humidity we had only covered 40 miles and my friend succumbed to heat exhaustion and became incapacitated. We had come too far to turn around to seek assistance, so the only option for a rescue was to advance further to the northwest to reach the Galvez River near the Matsés village of Nuevo San Juan.

Splitting up and leaving a guide with the injured person, I and another member of the party set out to reach the village of Nuevo San Juan on the Galvez River to seek help from the villagers. We banged on the buttress of a large tree to get the attention of the people in the village, at the time this seemed pointless to the point of absurdity, but within an hour a dugout canoe appeared with several Matsés. I went back to their village while two young Matsés went to rescue my injured friend. To this day I have no idea how they managed to carry him across the small logs and numerous obstacles to reach the river. By mid-night they arrived at the village with my friend.

Dave’s house in San Juan©Acaté

The Matsés welcomed us to their village, fed us, and treated our injuries with traditional medicine including the acate, the secretions of the large tree frog Phyllomedusa bicolor. They gave us a small traditionally built house to stay in on a bluff overlooking the river and surrounded by a beautiful garden. This hut was large and constructed without any nails or boards in the fashion of a traditional Matsés longhouse, with a high thatched roof for ventilation. The Matsés remarked to us that this house was built by a foreigner who had rapidly learned their language and customs. At the time, it was difficult to comprehend this claim; but many years later, I learned the house was built by David Fleck, who would later become a major part of the Acaté team.

Antonio, and his son, from the village of San Juan©Acaté

Once my friend had recovered, the Matsés were kind enough to take us down river to Angamos, a Peruvian military outpost on the Javari river along the frontier divide between northeastern Peru and Brazil. There, we hoped to find a seat on one of the sporadic military flights back to Iquitos. During the week-long wait for a flight, I contracted leishmaniasis, carried by the relentless biting sand flies. After a two-week course of treatment in the hospital I made a full recovery. I never forgot the kindness and generosity the Matsés showed in saving us and set an intention to reciprocate someday if possible. Those same Matsés involved in our rescue have participated in many of Acaté’s projects and remain friends to this day.

Bill Park of Acaté©Acaté

Years later I went back to Peru to complete the trek as originally planned and was fortunate to meet my wife, Carla Noain. After living for some time in Santa Cruz, California, we moved to Iquitos, Peru to build our company Eco Ola. Eco Ola specializes in restoring degraded/deforested land with highly diversified agroforestry systems to improve the livelihoods of indigenous communities and small farmers. Some of the superfoods we produce include sacha inchi, macambo, aguaje, and dragon’s blood. We might be best known for introducing macambo (Theobroma bicolor) to the world market. Once we were established in Peru it opened up the possibility of adding the NGO with a base of operations in the Amazon.

Acaté Co-Founder Christopher Herndon (Chris)

My own journey in Amazon had its own beginnings over two decades ago when, in the summer of 2000, I spent two months in a village deep in the Suriname rainforest close to the divide of Brazil. I had come to this remote village as a medical student to study the medicinal plant knowledge from the last remaining elder shamans of the Trio tribe, an indigenous group that was largely isolated before sustained contact with the outside world was initiated in the late 1960s. The rivers of the Guiana Shield, more so than the rivers of the Amazon Basin proper, are punctuated by rapids that hinder river travel into the interior. Due to their extreme geographic isolation, at the time of contact, the Trio had less exposure to viral pathogens than any group studied except for one group of islanders from a Pacific atoll. In 2000, Trio communities were still only accessible through an air strip cut from the jungle. Much had changed, however, in the few decades since they were first contacted by evangelical missionaries. Many aspects of their culture had been abandoned or suppressed, including their traditional systems of health by the evangelical missionaries on the grounds that it was “witchcraft”. As a result, for decades, none of the Trio elder shamans had apprentices.

In my undergraduate studies, I learned that many important pharmaceuticals had a history of use of traditional healers and that this knowledge was rapidly lost following contact with the outside world. I made a personal commitment that once in medical school I would work on a project to document this medicinal plant knowledge before it was lost. As you can imagine, finding this opportunity at that time was not easy. After months of writing letters, through dogged perseverance and with a bit of luck, I was fortunate to connect with a conservation organization active in the Northeast Amazon. The timing was fortuitous as the organization had just been contemplating developing a program to build traditional medicine clinics in partnership with the health care provider in the region. My interests coupled to my background in medicine seemed just the right fit. I am deeply grateful for the opportunity that would change my life.

Chris Herndon of Acaté©Acaté

The Amazon is a land of superlatives. As a twenty one year old medical student who had long dreamed of, but never set foot in, the Amazon rainforest, I prepared for the trip in every way I could, from learning everything I could about the ecology of the rainforest to how to best tie up a hammock in the jungle. From my reading, I knew that indigenous knowledge of the rainforest is extraordinary. Once in the rainforest and in their presence, I felt that the even the best books I read somehow fell short on conveying just how incredible their knowledge is as well as their wisdom, their kindness, sense of humor, and generosity.

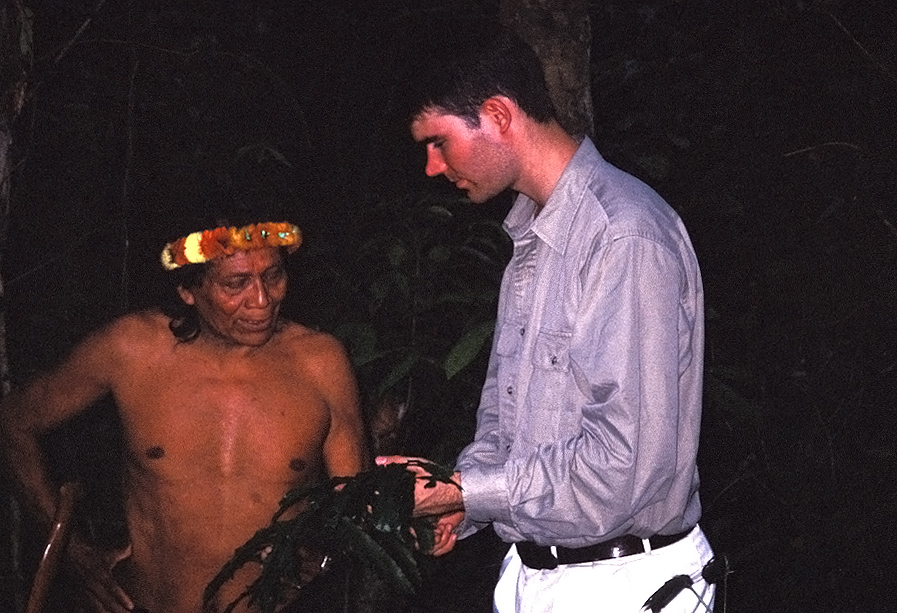

Chris as a student in the Suriname rainforest, 2001©Acaté

On long rainforest treks, Trio elders shared with me not only their use of medicinal plants from the rainforest, but also their diagnosis and management of various disease conditions. At that time, few scientists had attempted to rigorously study the understanding of disease and diagnostic concepts by Amazonian indigenous cultures; most had approached through the lens of their own botanical or anthropological backgrounds. In hindsight, it made no sense that these cultures would possess such incredible therapeutic knowledge of medicinal plants without a comparably well-developed understanding of disease to guide their use. Over a period of five years, I collaborated with Trio healers to describe and articulate translations of their disease concepts and anatomical terminology. I always approached the elders with the respect and humility of a student.

Over the course of the next four years, I traveled to Suriname many times and developed friendships. In addition to the Trio, I learned from other indigenous groups in the region, including the last remaining members of the Akuriyo tribe. The Akuriyo had been contacted in 1969, just a few short months after the publication of an anthropologic treatise on the Trio in which the speculation by the Trio of their existence was commented to belong “with the other extraordinary people who dwell only in the Trio’s imagination”. At the time of contact, Akuriyo were noted to be one of the very few tribes in the 20th century to still use stone axes (even “uncontacted” tribes often have in their possession old machete blades stolen or traded from neighboring tribes). Like some tribes such as the Heta, the Akuriyo were fragmentary remnants of larger tribal groups that had been devastated, decades or centuries previously, through introduced disease brought by early contact. Their transition to a nomadic hunter-gatherer lifestyle, avoiding large rivers to evade detection, was a survival adaptation. Tragically, as with the Heta, nearly half of the Akuriyo perished from disease in the first year following contact.

In the backdrop of the rapidity of disintegration that often follows contact from the outside world, Professor Richard Evans Schultes, the Harvard ethnobotanist who inspired so many, made a call to action “to salvage some of the native medico-botanical lore before it becomes forever entombed with indigenous cultures that gave it birth.” I understood the context but I believe the focus, in the here and now, should be maintaining these systems, not for the benefit of the world at large, but first and foremost for the indigenous communities themselves. Total loss of indigenous culture need not be a foregone conclusion. Also, if their medical knowledge can be saved, it would most definitely not be through a scientific publication in English, but rather only through active practice, as with any healing system. The result of the loss of traditional systems health in remote Amazonian communities is devastating and results in a near total dependency on the extremely rudimentary and limited external health care that is available in such remote and difficult-to-access locations. Sometimes people in the United States think of “Western” medicine, tertiary medical centers in metropolitan areas come to mind; the health care realities in remote Amazonian villages, without resources, electricity, supplies or infrastructure, is something quite different. Amazonian traditional health systems and use of medicinal plants are a collective of wisdom and experiential knowledge honed over centuries to address afflictions commonly encountered in the jungle environment.

In Suriname, we collaborated together with Trio indigenous elders and the regional health care provider to set-up traditional medicine clinics, with a goal of integration of care with the health outpost. At the start, funders and international health organizations were reluctant to provide financial support for the project. A great idea, they would say, but these types of projects inevitably fail. To be fair, this had largely been true in most cases. Our approach, however, was different. The framework of this program was simple: traditional medicine clinics, entirely operated and directed autonomously by the elder healers, built adjacent to the health outposts staffed by community health workers, so both clinics stand on equal footing in the community.

At the inauguration ceremony of the opening of the first clinic, Trio elder healers spoke with powerful oratory to the importance of carrying on their ancestral legacies. Breaking the long hold of suppression by the missionaries, the elders proudly stood and proclaimed, for the first time in decades, that they were healers. After the ceremony, I decided to catch the last seat on the bush plane returning with my colleagues to the capital city of Paramaribo so the indigenous healers could structure and operate the clinic fully on their own terms. On my return, as the bush plane circled in its approach to make its landing on the strip carved out from the jungle, I could see lines of people waiting to receive care outside of the traditional medicine clinic. The program proved an extraordinary success. Recognized by UNESCO as a Best Practice for Indigenous Knowledge, the program was cited as “an extremely impressive example of integration of the two systems of health”. With both systems of health placed on equal footing and prestige, what evolved organically was a true collaboration of traditional healers with regional health post workers, to the benefit of the community which could receive and benefit from the best of both systems of health.

I took many lessons to heart that years later would guide Acaté but will highlight here two: 1) the program succeeded whereas others had failed because the program was entirely placed in the indigenous hands. Top down projects are doomed to fail. 2) As any one who has operated in the difficult domain of conservation knows, it can be all too easy at times to lose hope, to view the powerful forces driving environmental destruction and cultural degradation as relentless and unstoppable. In starting Acaté with Bill, I thought back about what was accomplished in that village in Suriname to remind myself that real positive change in trajectory could be achieved with the smallest amount of resources, if done the right way.

Through my volunteer work with the conservation organization as a medical student, I was fortunate to visit and learn from a number of indigenous healers and communities across the Amazon, from the taita shamans of the Colombian Putumayo to the Alto Xingu of Brazil. I took an extra year of medical school after completion of all my clerkships to collaborate with a husband and wife team of anthropologists from the Instituto Venezolano de Investigaciones Científicas to initiate a program for culturally inclusive health provision for isolated nomadic groups of Hotï, the last tribe to establish sustained contact to the national culture of Venezuela. The groups of Hotï were divided between those that lived in mission settlements and those that did not. The mission settlements offered access to medicines and steel goods but at the price of abandoning many aspects of their culture and ways of life, even to the extent of their songs and dances. The non-mission Hotï groups lived nomadically and maintained a pretty much intact traditional way of life but struggled with high disease burdens from introduced pathogens and no access to medical services. The regional health authorities hardly knew they existed.

©Acaté

The project, in partnership with a regional health organization in Amazonas state, was to set-up health outposts and vaccine programs in strategic locations to reach the Hotï groups so that they did not need to make a choice between their health and their culture. To first reach these groups to consult them in the development, we needed to fly to a small air strip cut just at the foot of the highlands that no sober bush pilot wanted to land on. We then trekked on foot into the highlands in search of the nomadic groups. After several days we were fortunate to finally encounter a group of Hotï stalking a troop of spider monkeys with twelve foot long blowpipes. The project got launched but was disrupted a year or so later by the escalating political and economic instability that set in the country at that time. Years later, my colleagues and friends in Venezuela, a country still beset today with enormous challenges and adversity, persisted and developed a malaria prevention program involving all of the Hotï communities. They, and the many indigenous and non-indigenous people who struggle selflessly on-the-ground to make a difference without public fanfare, are my heroes.

After the Venezuela project, I began seven years of residency and fellowship which made travel to remote areas of the rainforest for the most part logistically impossible. I spent my hours in the hospital library post-call writing up my research with a commitment to one day return to the Amazon. It was a deep longing but, most of all, I felt a personal obligation to give back to the indigenous communities and do my best, with the experiences I had been given and the knowledge that had been shared with me, to help them as best as I could in their pressing struggles.

In 2010, I met Bill at a Bay Area Tropical Forest Network meeting at Stanford University, where I had been invited to give a talk on my research on the healing knowledge of Amazonian indigenous healers which had just been published.

The Founding of Acaté (2011 to 2013)

After Chris’ presentation at Stanford we talked and shared our experiences in the Amazon. We got together several times to kayak in the ocean off Santa Cruz, California and continued our discussions. Antonio, one of the Matsés who had rescued Bill’s friend, had extended an invitation for Bill to return and visit the community of Nuevo San Juan. Bill, who had moved to Iquitos, Peru (gateway city on the Peruvian Amazon), invited Chris, who was just completing a long stretch from seven years of residency and fellowship, to come to Peru and visit the Matsés together.

In July 2011, we flew on a small float plane from Iquitos to Angamos. At that time postponed military civic flights were more the rule than the exception, so we were delayed to an indeterminate time later in the week. At the last minute we were able to charter a small four seater float plane but needed to jettison much of our supplies due to the weight restrictions on the small plane. Antonio met us in Angamos and took us upriver to San Juan where they spent several days as guests of the community.

Matsés village of San Juan©Acaté

During our trip, we took stock of the Matsés situation and the absence of external support. Antonio discussed the lack of economic opportunities in their communities. Outside of a handful of better paying jobs for school-teachers, the only economic opportunities available were cutting timber, which is quite dangerous work, and low-paying, at times not paying at all due to scams. Many younger Matsés men would leave the community to seek minimum wage jobs in Iquitos, not earning enough to send back remittances to their families and sometimes not returning at all. The Matsés faced many pressing challenges and there was a void of initiatives that were guided by the stakeholders who best understood their own problems.

Antonio was particularly concerned by the dire status of their health care. He told us that sick Matsés would often not be flown to Iquitos for emergency care until it was too late, and then they would languish in the public hospital without their accustomed food, translator or social support. The families would be responsible for the cost of repatriation of their remains if they died, for which they usually would not have money. Antonio showed us the simple structure that served as the community’s medical post and we saw that the medicine cabinet was bare. He showed us with pride the medicinal plant garden (Healing Forest) created years earlier by his father, perhaps the most renowned of all Matsés plant masters, who had recently passed away. Even as the village heavily relied on plant medicines, the young people had no interest in learning about their traditional medicine. No Matsés elder, not one, in any community, had an apprentice.

We finished that trip with a long list of challenges that the Matsés faced but we had no clear way to work with them or provide support. Antonio explained to us that a lot of the Matsés population lived on a small river, the Chobayacu, that flowed parallel to the Galvez further to the east (good maps of the Matsés villages were harder to find back then). Antonio proposed we visit these communities on the Chobayacu.

The next year, 2012, Antonio arranged an invitation for us from the Matsés communities on the Chobayacu River. The Chobayacu is the heart of the Matsés Ancestral Territory and at that time the communities were largely closed off to outsiders. This was understandable as the sum of their experiences with the outside world largely consisted of proselytizing missionaries, timber cutters who left with valuable timbers with a promise to come back and pay later; organizations who visit once, take pictures of the Matsés in their traditional attire, then fundraise online for projects that simply would never materialize, and governmental agencies mandated by law with ear-marked funding to provide social support but would show up empty-handed, claiming poverty.

This trip, we were able to take the military flight to Angamos where our friend Antonio greeted us and took us upriver in his peque-peque (dug-out canoe with a long shaft motor). Based on the empty shelves we observed in the medical post on our previous visit we bought two boxes of medicines purchased in Iquitos to donate to the medical outposts. Looking back we could say this was our first donation to the Matsés. After a couple days exploring the upper Yaquerana (Javari) River, which forms the border of Peru and Brazil, we turned westward and entered the Chobayacu River. Two hours from the river mouth sits the Matses village of Estirón, where David Fleck lived.

Dave is an exceptional person. He was born in Lima, Peru, but grew up in Ohio in the United States. While still an undergraduate Dave received a grant to study mammals near the Ucayali River town of Genaro Herrera. Returning to the area in the early 1990s for his master’s thesis in zoology on arboreal opossums, Dave encountered Antonio and the Matsés in the community of San Juan, as Bill would years later. The Matsés treated him so warmly that he switched his area of focus from zoology to linguistics so he could spend more time with the Matses. For his PhD thesis, he wrote the first grammar of the Matsés language. The next year Dave co-authored a book on Matsés culture in their own language.

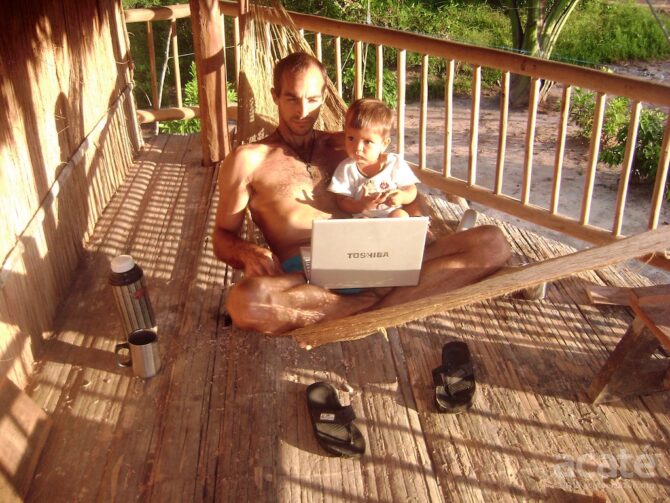

Dave Fleck and family©Acaté

For a decade after, Dave lived in Estiron with his Matsés wife and two boys as an integrated member of the Matsés community. Over that time, he published over 30 scientific publications on the Matsés culture, biodiversity, and language.

Dave Fleck and his Matsés history instructor, Manuel Tumi©Acaté

It was incredible to see the way Dave, a highly accomplished academic linguist who had turned down a prestigious faculty position, was living in a traditional Matsés way. He hunted, cut and maintained a farm that provided all the food his family needed. He had built his house out of traditional materials using no nails or boards. He even grew his own coffee. Dave is incredibly fit – remarking that due to his jungle lifestyle he did not need a gym membership like he had when he was studying at the university. We learned a lot from Dave about the current Matsés situation and their history. We asked Dave if he might consider helping us with any future projects and he agreed.

Dave Fleck of Acaté©Acaté

Before we headed further upriver, Dave loaned us his ax and said we would need it to cut the trees that had fallen over the river if we hoped to reach the largest Matsés communities. This saved our trip. It was the peak of the dry season and water level of the small river was exceptionally low that year. Every few hundred meters we needed to get out of the canoe and cut the obstructions to advance.

Finally, we started seeing canoes by the side of the river and the happy voices of children playing on the river bank under the sun. We arrived in Buenas Lomas Nueva, a bustling village of over 500 people. It struck us that, in the middle of a vast expanse of jungle in all directions, the Matsés had built their largest community, so far removed from the outside world.

©Xapiri/Tui Anandi/Mike van Krutchen/Acaté

In Buenas Lomas Nueva and all the other Matsés communities we visited we held meetings that often extended late into the evening. The Matsés shared with us that their greatest concerns were for their children and their future, particularly the lack of health care, poor education, and the absence of economic opportunities to support their families. In each community we heard the same accounts of the absence of external support, chronic disappointments, and the lack of consideration for the Matsés’ wishes. The situation for the Matsés communities could be summarized as being trapped between opportunistic and predatory extractive industries, chronically corrupt regional governments that embezzle state funds, and by top-down NGO programs that where either ineffectual or outright scams. For those living outside of the Peruvian Amazon, this reality might seem jarring and at odds with global consciousness and support of indigenous peoples seen constantly in media, but the reality on-the-ground is only a trickle of conservation funds make it down to the indigenous communities. The Matsés, as with many indigenous communities in the Amazon, struggle with the most limited external resources.

The communities asked for our support and we committed to launch Acaté. We choose the name of acaté in recognition of the ceremonial use of the secretions of the frog Phyllomedusa bicolor, a unique aspect of the Matsés and a few other related Panoan groups’ cultural heritage. At that time, the use of Phyllomedusa bicolor secretions was not well known to the outside world apart from some anthropologic reports and a handful of popular magazine articles here and there. We could not have imagined that in a few short years later, the use of Phyllomedusa bicolor secretions for healing would explode on the global scene. Fortunately for us, another indigenous-derived term, kambo, rather than acate, became the popular nomenclature otherwise we would have likely had to rename our organization to avoid confusion!

Acaté’s logo with the Phyllomedusa bicolor frog was designed by the gifted illustrator David Julian. We learned later that David had also created, years earlier, the famous Rainforest Alliance frog logo seen ubiquitously today on packages in grocery stores.

Building Acaté (2013 and Onwards)

With Bill and his wife Carla Noain established in the gateway city of Iquitos, the largest city in the Peruvian Amazon, and the largest city in the world without road access, we had an anchor point in the Amazon. Carla is a Peruvian eco-social entrepreneur with expertise in regulatory compliance, logistics, and community relations. She grew up in Lima, but moved to Iquitos as a teenager when her father was transferred to Iquitos by the Peruvian Air Force. As a student she worked on educational projects with communities around Iquitos and developed a deep appreciation for the people of the region and the challenges they face.

Carla Noain of Acaté©Acaté

The two most common pitfalls to set-up a conservation organization in Peru are the bureaucracy and misunderstandings with community stakeholders. Opening the Peruvian organization, really anything in Peru, meant generating stacks of papers, and getting each document stamped by a labyrinth of government agencies. Even simply opening a bank account is not a trivial exercise. In contrast to requirements in the United States, Peruvian organizations are also required to file income tax reports on a monthly basis and all purchases made are cross referenced with the seller’s tax filings. Any discrepancies can lead to large fines. Thanks to Carla, we were able to navigate all these obstacles and set up procedures to function with this complex system. Having an office space, donated by Carla, enabled us to work with the Matsés that come into the city, and provided a much-needed link for their communities to the outside world.

Once the Matsés learned that there was a new organization interested in working with them, their Jefe (elected chief), Sabino Tumi visited us in Iquitos. He had no place to stay so we invited him and his family to stay with us. Sabino was very concerned about a pledge of major support from an international funder that had never arrived. He had the name and email of the funders point of contact, a person who had visited the Matsés, so we helped Sabino compose a message inquiring about the funding for the Matsés. Unfortunately, the funder wrote back and said the funding had been given to a Peruvian indigenous federation that claimed to represent the Matsés. To this day, despite frequent postings on social media that this organization is “working” with the Matsés, they have never carried out any actual projects with the Matsés. Sabino’s other concern was in respect to a potential tourist program to bring jobs to the communities that were open to hosting visitors. Earlier, a prominent Peruvian NGO had received a significant amount of international funding to build a tourist lodge upriver from the Matsés communities on the Galvez River, that included solar panels, tiled showers, and all the conveniences an international visitor might expect. The goal was to create economic opportunities for the Matsés. The lodge was constructed. The problem was there was zero investment in marketing or outreach to attract tourists, or to address the considerable logistical issues such as developing more reliable ways for international tourists with fixed itineraries to reach the Matsés territories as the military civic flights were so unpredictable. Trained groups of young Matsés were told by the NGO to simply wait in this facility, in one of the most remote corners of the Amazon, for tourists who would never come. Their concerns were not heard and the project at the start was doomed to failure.

We knew that we had to build initiatives that were truly led, coordinated, and undertaken by the Matsés people themselves. This is why our initiatives over the past decade have been successful. Our website details the structure of our organization, which is a precise accounting of how we operate. This workflow and hierarchy is significant because at that time we launched our website in 2013, public messaging of many conservation organizations was still focused on saving the rainforest and native communities were an afterthought. Further, we felt the focus in the public representation and messaging needed to be on the Matsés and the frontline work, not on our staff. Since that time, mainstream conservation messaging in the public domain for many organizations has shifted noticeably in this direction towards a focus on indigenous rights and representation; how much this has led truly to a change in organizational practices is debatable.

We were joined by the incredibly talented graphic design artist Tigre, who lived in Peru and was involved in community-level permaculture activities and he built our website. We did not have a fundraising network at the outset so nearly all of the funding for Acaté’s start-up and first couple years came from our own pockets and limited resources. Noah Sabich, Ph.D., who had recently finished his doctorate in Tahiti studying post-colonialism, joined our volunteer US team. Noah worked together with Chris on grant writing and drafting our 501c3 application. Noah continues to spearhead our social media page.

Noah Sabich of Acaté©Acaté

Mongabay.org served as our fiscal sponsor until we received notice of approval of our 501c3 application status in March 2014. In 2014, we received our first foundational grants from the Conservation, Food and Health Foundation and the Irwin Andrew Porter Foundation. We are deeply grateful for their early support, and that of others who had faith in our organization and gave us our start. Their support made all of this possible.

How We Work

Acaté exists to support the Matsés in protecting their lands, culture and way of life. The unifying theme of all of Acaté’s programmatic areas is self-sufficiency. The Matsés know the best way for them to protect their culture and lands is through a position of strength and independence. The reason why the Matsés lands – which comprise over 95% intact primary rainforest – exist today is because the Matsés have actively fought the incursions of outsiders, from the rubber tappers of old to modern day multinational petroleum companies. There is a strong correlation between intact ecosystems and regions of indigenous inhabitation, making strengthening of indigenous culture the most effective way to protect large areas of rainforest. The territory that the Matsés communities protect is a critical part of a large binational corridor of global significance that shelters the largest number of uncontacted tribal groups in isolation remaining in the world.

At a Matsés assembly one of the renowned elder Matsés shamans and famous warrior Arturo stood up and spoke in oratory in support of Acaté. He stated that unlike other organizations, Acaté does not come to tell the Matsés what to do; we ask the Matsés what they need, involve the Matsés at every point, and listen to their ideas. He described us as a different type of outsider and ones that they were glad to work with- we could not think of a greater accolade. Arturo is pictured here addressing to assembled Matsés concern for governmental encroachment into their Ancestral Territory that came to light in the Matsés Indigenous Mapping Initiative.©Acaté

When we started Acaté, ten years ago, the only way to communicate with the Matsés from Iquitos was by short-wave radio from a radio booth in the notoriously crime-infested and grimy river port of Masusa on the outskirts of Iquitos. Even with two Matsés communicating or Dave translating, it was always very frustrating trying to hear what was being said through the static. To make matters worse, Matsés communities often did not have functioning radios.

©Xapiri/Tui Anandi/Mike van Krutchen/Acaté

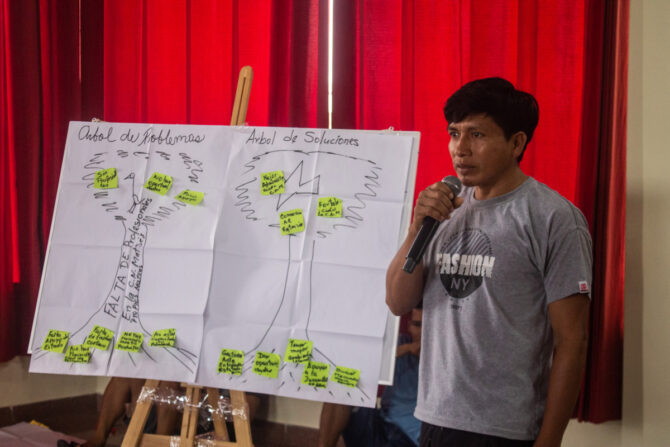

Because the Matsés have limited radio communication between the communities, some communities three days apart by river travel, meetings are the most important means of sharing information and organizing. Under Peruvian law the maximum authority for a native community is the general assembly or assemblea. The delegates to the assembly are elected by the community and the numbers of delegates from each village are proportional to the population. One delegate represents seven adults. Anyone in the community can attend.

Except during the time of the pandemic, we sponsored an assembly meeting each year to share the results of the previous year and plan the upcoming years’ projects. The meetings are big productions that require much advance planning to properly coordinate the fuel, meals, presentations, and making sure all the villages receive the invitation letters. The Matsés are very grateful for our presentations that include the project expenditures and especially the budgets for the upcoming year.

Not all the meetings went as planned. Obstacles have included unpredictability of weather impacting the departing flights from Iquitos (pretty much most of our trips), canoe sinking, and snake bites. Even less anticipated was an Australian reality TV show that had chartered the military civic planes, stranding us in Iquitos and nearly causing us to miss the meeting.

Bill and Chris at an Acaté assemblea with the Matsés, 2017©Acaté

A common question we get asked is whether there is cell phone access in this remote area of the Amazon. At the time Acaté started, there was no cell phone coverage or internet in any part of the Matsés territory. In recent years, mobile coverage arrived in gateway military outpost of Angamos and even just marginally to the nearest Matsés community closest upriver to Angamos. In respect to the latter, a few years ago when Bill was meeting the Matsés chief who had just flown in to Iquitos, the Matsés chief commented that our field coordinator was waiting for Bill to call him. Bill asked “Is he in Angamos?”, the Chief replied that “No, he is waiting in his tree”. This left us scratching our heads until we learned that our field coordinator had climbed to the top of a tree outside of that village to capture the faint cell signal and was sitting there, perched at the top of the tree, waiting for a call from Bill. Today, two schools in Matsés territory have satellite internet connections that are made public for a few hours a day, but there is still no cell phone coverage or internet in most of the territory.

For coordinating between our teams in the US and Peru, communication in the early years of Acaté was largely through planned Skype calls, which was cumbersome as the connection was often fragmented particularly during rainstorms. Years later, Whatsapp and better internet in Iquitos has made messaging instantaneous and we confer daily.

Traditional Medicine Encyclopedia

Our first major initiative was to aid the Matsés in preserving and transmitting their traditional healing knowledge. As Chris’ noted earlier, for centuries, Amazonian peoples had passed on through oral tradition an accumulated wealth of knowledge of the natural world. With cultural change destabilizing even the most isolated societies, that knowledge was rapidly disappearing. As a result of these outside influences, the remaining Matsés elders, now all over 60 years old, had no apprentices among the younger generations. Their ancestral knowledge was poised to be lost forever. Once extinguished, this knowledge, along with the tribe’s self-sufficiency, would never be able to be fully reclaimed.

What has followed the loss of endemic health systems among indigenous groups living in remote and difficult-to-access locations is a near total dependency on the rudimentary and extremely limited external health care that is available in such settings.©Acaté

Despite the lack of apprentices, most Matsés villages still actively depended on and utilized the medicinal plant knowledge of the remaining elder healers as a primary source of health care. How does one revitalize an entire system of healing? Fortunately Dave’s father in law, Lucho Jimenez, is one of the remaining living Matsés elder plant masters. Dave and Lucho took many walks together in the forest and they devised a plan to write an encyclopedia. Each elder shaman would be paired with two young Matsés, who had been schooled by the missionaries to write in a written articulation of their language. One young Matsés would record the information from the elder and photograph the plants, and the other young Matsés who would work to digitize the chapter. Importantly, the encyclopedia was going to be written only in the Matsés language.

Boarding the jungle plane to travel to Matsés territory, 2015©Acaté

Two years later, at the end of May 2015, we traveled together to a historic meeting in the Matsés village in Puerto Allege, where the last remaining elder shamans of the Matsés tribe gathered together to review drafts and finalize the first volume of the encyclopedia.

The Matsés Traditional Medicine Encyclopedia marked the first time shamans of an Amazonian tribe have created a full and complete transcription of their medicinal knowledge written in their own language and words. Each entry is categorized by disease name, with explanations of how to recognize it by symptoms; its cause; which plants to use; how to prepare the medicine and alternative therapeutic options. A color photograph taken by the Matsés of each plant accompanies each entry in the encyclopedia. The Encyclopedia is written by and from the worldview of the Matsés shaman, describing how rainforest animals are involved in the natural history of the plants and connected with diseases. It was fully written and edited by indigenous healers, the first of its kind and scope.

Matsés review and edit drafts of the Encyclopedia at the meeting©Acaté

Due to concerns over bioprospecting, prevalent in the international community at the time, we knew that we could not have digital copies available. For the printing, we found an old fashioned book maker in Lima and arranged to have the books sewn and pressed by hand. The Encyclopedia once completed was printed in two volumes, with each volume 500 pages in length.

For us, the highlight of the meeting in Allegre was seeing the gathered elder shamans sitting together and reading over their work. Instead of an outsider coming to document their knowledge, they had preserved their own medicinal knowledge in their own words. Seeing the elders react to the renewed community interest in their knowledge brought tears to our eyes.

On the return©Acaté

Shortly after he returned to the States, Chris did an interview for the project with Jeremy Hance of Mongabay.com, the world’s leading environmental news site. This interview immediately went viral globally and became one of the Mongabay’s top stories of all time, and today continues to circulate. Acaté was on the map in the conservation world and the Encyclopedia was our big break as an organization in terms of visibility, but the Encyclopedia was just the first step of a multiphase project. Just as studying a western medical textbook does not make one a doctor, learning the Matsés traditional medicinal system takes much more than book study. Indigenous healing systems, like all healing systems, are based on experience that can only be transmitted through long apprenticeships. This was true when the Matsés elders learned from their fathers and grandfathers before them.

Nestor Bina, a Matsés elder from the community of Puerto Alegre, was involved in the peaceful and permanent contact the Matsés had with the outside world in 1969.©Xapiri/Tui Anandi/Mike van Krutchen/Acaté

At the meeting in Allegre it was agreed that the next phases of the project should involve making the medicines more accessible and advance the training of the next generations of Matsés healers. This second phase involved creation of Healing Forest Medicinal Plant Gardens, based on traditional Matsés agroforestry. For many, the term medicinal garden might connote a sun-exposed garden adjacent to a house or a farm clearing. Many of the rainforest vines, tree saplings, ferns and fungi that the Matsés use daily for healing will not grow in sun-exposed gardens. They require rainforest ecosystems for their propagation, adding considerable levels of complexity and challenge. It is important to also understand that the Healing Forests are not a new introduction but a restoration of traditional Matsés agroforestry practices that fell into abandon following sustained contact with the outside world. For generations, Healing Forests had supplied the Matsés communities with an abundance of sustainably sourced medicinal plants to treat urgent health needs. The benefit of having the plants nearby, especially the rare ones, provides both a classroom for teaching and access for treating patients.

To an outsider, this forest might appear to be a nondescript stretch of rainforest along a footpath to their farms. In the presence of a master shaman pointing out the medicinal plants, you realize in a moment that you are surrounded in fact by a constellation of hundreds of medicinal plants cultivated by the Matsés healers for use in treatment of a diverse range of ailments.©Acaté

These factors made the decision to re-establish Healing Forests an easy one. Each village selected twelve individuals to participate along with an elder healer and an Acaté field coordinator. For villages without an elder healer in residence they arranged for one to travel from another village. Over the course of the next two years, Healing Forests were restored in all of the Matsés communities. The best students were selected out of the participants to participate in the Advanced Internship program. The advanced interns traveled in groups of two or three to the villages of the elders for more focused work with the elders on diagnosis and treatment of patients. This program has experienced some funding gaps but remains ongoing today. We are planning a major expansion for 2024.

Teaching in a Healing Forest; a young Matsés uses his cell phone to record the teaching of plant master Lucho ©Acaté

Sustainable Economy

To achieve any level of success, a conservation organization must operate from the vantage point and be guided by local communities. Far too often, even well-intentioned conservation initiatives do not address the real-world drivers of the destructive activities and create viable economic alternatives where few exist. Even the most remote and traditional indigenous communities, such as the Matsés, have been drawn into the cash economy to buy the basic household items they need for their families. They do not want to have anything to do with timber, which is a difficult, low-paying and dangerous activity, but where are the alternatives for their communities? For this reason, Acaté and the Matsés positioned sustainable economic development as a foremost operational priority or pillar, along with health and food security.

One of Acaté’s earliest projects after the founding of the organization was the Copaiba or Renewable Resins project. The golden amber-colored resin of this slow growing canopy tree has quite valuable medicinal properties and is also used in personal care products. The trees have been extirpated in most of the areas around Iquitos for the valuable hardwood, most commonly for furniture. In the rainforests protected by the Matsés, copaiba trees are present in several areas of their territory, particularly upland forests with high densities of trees from the family Lauraceae, called moenas locally in the Peruvian Amazon.

©Acaté

At the start of this initiative, we had read papers extolling the potential virtues of copaiba as “the diesel tree”, claiming that the copious amounts of resin that could be easily extracted and used as a biofuel. We found out these narratives to be out of touch. Resin production is not particularly copious and most certainly is not easily extracted from cavities deep in the center of dense hardwood of the tree. In frontier areas of the Amazon, copaiba resin is typically harvested by cutting a large wedge into the tree trunk with an ax, which will ultimately lead to the tree’s demise. There was very little experience in the sustainable harvest of copaiba resin so we set out with Matsés to figure this out on our own. We could not find any suitable drills so we created our own. We bought the largest drill blades we could find off the shelf and then had iron rods welded on as extensions. With our new drills, collection, vessels, and even alcohol to sterilize the equipment to avoid infecting the tree, Bill and Dave set out with the Matsés to develop the best approaches for sustainable harvest. The drilling was laborious taking about 30 minutes per hole because the trees were two meters or more in diameter of dense hardwood. The drill blades are only twelve inches so the bit does not expel the saw dust properly after twelve inches of depth. The first two attempts yielded nothing but blisters on our hands. Luckily on the third tree we hit a seam with resin and were able to collect about a half liter. Over time Matsés have further refined the techniques, learned the correct trees, approaches, and optimal seasons for collection. One important note is that the holes must be plugged tightly, some type of hardwood plug is best, to avoid infections and to allow the resin to build up behind the plug. This project has been successful and expanded to multiple communities of the Chobayacu. The demand, even locally in Iquitos, continues to exceed our ability to supply it.

Sustainable harvest of valuable copaiba resin©Xapiri/Tui Anandi/Mike van Krutchen/Acaté

Sustainable economic development continues, and always will be, to be a primary pillar of Acaté’s work. In 2016, we partnered with Xapiri Ground to develop a successful handicrafts project, which includes traditional bracelets called uitsun, lances and ceramics. This project had its origins in one of our assemblies with the Matsés held in the village of Buen Peru. Toward the end of the meeting, Carmen, a Matsés woman from that community, stood up and addressed the assembled leaders from the 14 villages and the Acaté team. She pointed out that the economic programs developed with Acaté so far, such as the sustainable harvesting of copaiba, have centered largely on activities done by men. She pointed out that Matsés women have valuable skills and want to contribute to developing economic opportunities for their families. Carmen held up a handful of beautiful woven friendship bracelets called uitsun by the Matsés. Although these bracelets are still worn by the Matsés as accouterments of daily life, Carmen lamented that the knowledge of their craft was not being passed down to the younger Matsés women.

While the passion and commitment for this project was strong, the market demand for their exquisite and beautiful handicrafts simply did not exist at the time. Over the decades, conservation organizations in the Amazon have launched many well-meaning handicraft projects. With a few exceptions, most fall short of realizing true economic viability due to the lack of demand and do not get past the early stages. A major reason is the lack of global market for Amazonian handicrafts, which was not as well developed as for artisanal objects from other regions of the world. Another problem from perspective of the communities is that handicraft initiatives with indigenous groups living in remote areas of the Amazon typically source from only a small handful of individual artisans located in the most geographically accessible villages. The Matsés are an egalitarian people and they have reiterated to us on all of our projects the importance of involving as many members of their communities as possible so that the benefits can be equitably shared.

©Xapiri/Tui Anandi/Mike van Krutchen/Acaté

The project is now in its seventh year and continues to go strong. In our partnership with Xapiri, the Acaté team coordinates all the purchases, quality control, and transport of artisan crafts from the Matsés territories to Cusco, Peru where Xapiri is based. Xapiri is responsible for developing global awareness and market for these crafts (which did not exist when the project started), and the retail sale. The Xapiri team (Jack Wheeler, Tui Anandi, and Mike van Kruchten) traveled with Acaté to the Matsés communities and produced an exquisite three-part reporting on Matsés culture called Ancestral Transmission, as well as galleries and exhibitions that promoted Matsés culture and cultural products in collaboration with Acaté.

©Xapiri/Tui Anandi/Mike van Krutchen/Acaté

We continue to look to expand further this important initiative and seek international buyers for the Matsés beautiful and exquisite artisanal work. Please contact us or Xapiri Ground if you are interested.

©Xapiri/Tui Anandi/Mike van Krutchen/Acaté

Matses Indigenous Mapping Initiative

After completion of the Encyclopedia, Acaté’s next large project was the Matsés Indigenous Mapping Initiative. Before this initiative, the only maps of Matsés lands that existed were those created by non-Matsés that depict for the most part an empty landscape. A few scattered dots along the large rivers that represent their present-day settlements are the only indication of Matsés’ inhabitation. Only the largest rivers are named in Spanish. To the Matsés, the caretakers of these lands, the blank areas on these maps were not voids but the living heart of their territory.

©Xapiri/Tui Anandi/Mike van Krutchen/Acaté

Launched in 2015, the objectives of the Matses Indigenous Mapping Initiative were to demarcate the ancestral territories of the Matsés in Peru for the first time and geospatially record the Matsés’ worldview, culture, history, and descriptions of their rich ancestral landscape.

This project was simply daunting in scope and scale. For one, the Matsés Ancestral Territory encompasses almost 3 million acres of rainforest, that is an area larger than the state of Connecticut or about the size of Qatar. Secondly, and not a small point, no one of the Acaté team really had any actual experience in GPS mapping or GIS technology. We were reluctant to partner with outside organizations that might impact how we work with the Matsés communities so we set to the task of learning ourselves, together with the Matsés.

What would become an immense five year landmark initiative started modestly when Acaté purchased two GPS units off-shelf from an electronic retail store in Lima and brought them back with us to Iquitos. We arranged to have the GPS shipped on the military plane to Angamos, the Peruvian military outpost on the Brazilian border which is the gateway of the Matsés territory.

After training on the GPS use, the Matsés project leaders went on to map the headwaters of the Yaquerana (Upper Javari), the beginnings of a massive five year endeavor in which teams of Matsés, paired with elders and youths, went to the farthest reaches of their territory to demarcate for the first time the extent of their ancestral territories.

The initiative proved more time-sensitive than we had anticipated. At the start of this project, the Matsés’ rich knowledge of their lands and ancestral history resided only in the memory of their living elders. Most young Matsés did not know the names of even the larger rivers in Matsés. What we had not considered is that the elders who held the most knowledge were reaching an age where it is increasingly physically difficult to walk to remote cultural and historical sites, such as locations of long abandoned ancestral longhouses and sites of frontier skirmishes with Peruvian soldiers. If the project start had been delayed even by a year or two, an incalculable amount of information would have been forever lost. In the end, the Matsés ended up recording over 12,000 culturally significant data points.

Clay pots mark the site of a longhouse in the far reaches of the upper Galvez river that was hastily abandoned following a skirmish with Peruvian soldiers over 70 years ago. Before the Matsés Indigenous Mapping Initiative, important ancestral sites such as this resided only in the living memories of the elders.©Acaté

The goals for the Matses Indigenous Mapping Initiative extended beyond mapping their territory. Typically in participatory mapping projects, indigenous peoples were trained in the use of handheld GPS units to record culturally important mapping points. Particularly with projects involving recently contacted indigenous groups, the maps themselves were put together and created by partner organizations and NGOs with technical specialists with expertise in the highly complex mapping software. Media images associated with such projects, like a picture of an indigenous elder in a red loincloth in front of a laptop, belie the reality that computer literacy is obviously low among recently contacted indigenous groups.

Our goal was to provide training not only in use of handheld GPS devices, but in the use of GIS mapping software so that the Matsés could produce maps independently, thereby acquiring the ability to revise current maps or create new maps in the future. The challenge was that most Matsés at that time had not powered up a laptop, let alone had proficiency in the highly complex GIS software. There are courses at universities entirely devoted to the software. We started with basic computing classes and then advanced to software training. The Matsés learned so quickly and in no time exceeded our expectations and the project leaders ultimately outpaced our own proficiency. In the global consciousness, organizations particularly for fundraising purposes are quick to portray in their public messaging, either explicitly or implicitly, indigenous peoples as helpless victims who are incapable of helping themselves. This narrative is false and demeaning. The Matsés ask for our help as they struggle against enormous challenges with the most limited external resources – but they are independent and highly functional people. This is how they thrive in the Amazon rainforest, one of the most beautiful but difficult and unforgiving environments on the planet. They are among the most independent and resourceful people we have met.

Have you ever seen one of those reality shows on TV where some guy survives in the jungle for a few days, dirty, sweaty and eating bugs? In contrast, if Felipe, the Matsés in the photo, went into an unfamiliar part of the jungle after a week he would be living comfortably. He would have a nice hut with kopal resin lamps, lots of delicious fruit and fish and most likely a handmade hammock to relax in. Yet Felipe is also now proficient with advanced computing and would be equally comfortable in a work office in the city. Acaté’s initiatives bridge generations, inspiring youth that their identity as Matsés can lie in both traditional and modern systems. That to choose one is an artificial choice, one can thrive in the outside world, yet retain a proud identity as a Matsés.©Acaté

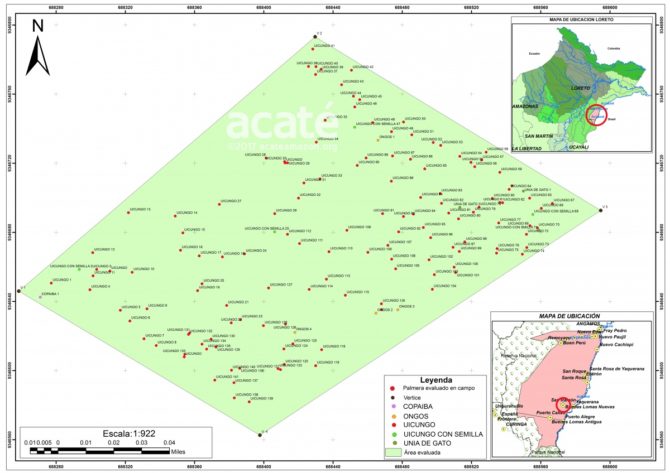

In August 2019, on the 50th anniversary of sustained contact with the outside world, leaders of the Matsés tribe of the Peruvian Amazon assembled to unveil the first completed maps that demarcate their ancestral territories. As a result of this mapping initiative, 144 Matsés were trained and received certificates in basic computing. Acaté went on to build the first computer lab in the Matsés territory. The mapping project has had many downstream positive benefits in providing the Matsés invaluable tools and capacitation for governance, accounting, developing the ability to develop the demarcation needed for management plans for sustainable harvest of non-timber forest products, to cite a few.

The export and sale of renewable non-timber forest products has the potential to bring much needed economic opportunities to the Matsés native communities. Legal export from Peru requires the creation of complex management plans, which involve GPS demarcation of each individual tree in the area that will be used for collection. The training in the mapping project conferred the ability for the Matsés to demarcate and generate this plot map of huicungo trees (murumuru) shown here.©Acaté

The completed maps of the Matsés Ancestral Territory along with all their cultural documentation enabled the Matsés to be the first native community in Peru to be internationally recognized as an ICCA Registry (Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities Conserved Areas and Territories) by the United Nations Environmental Program.

©Xapiri/Tui Anandi/Mike van Krutchen/Acaté

Despite this international recognition the Matsés land tenure situation remains complex. Within the Matsés Ancestral Territory there are two classifications for their titled lands, three classes of nationally protected areas, and a stalled area of titling expansion. The national protected areas each have buffer zones, regulated by separate Master Plans, that extend into the core Matses titled areas. In addition there are canceled, and active, petroleum concessions. To visualize all these overlapping zones and the frequent changes made to each one requires the use of a GIS system.

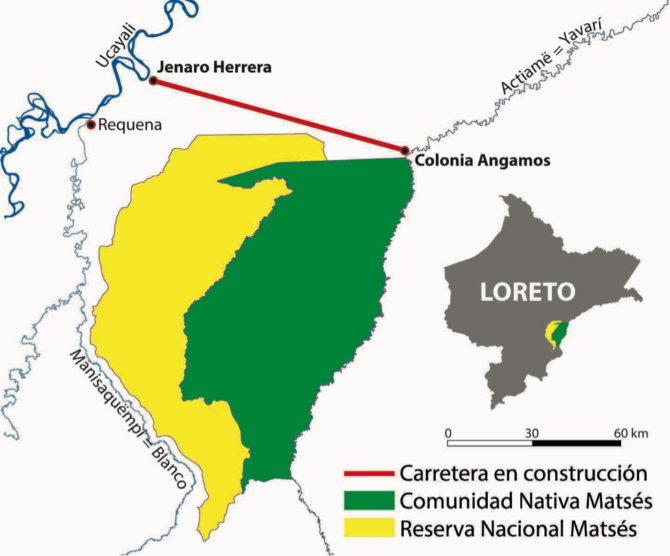

Planned road to Angamos that would open up access to Matsés territories.©Acaté

The Matsés continue to fight ever-present encroachment into their ancestral territories that comes in many directions, from prospect of petroleum exploration by oil companies in their headwaters when oil prices rises to make the prospect of remote extraction profitable, to the looming and existential threat of a road construction from Ucayali river to Angamos that would completely open up their territory – long sheltered by its geographic isolation – to settlers, to re-working of borders and accession of the government of portions or their ancestral territory to create parks without full consultation or consent of the indigenous communities.

In respect to the latter threat, in the minds of many, the creation of a national park or nature reserve automatically confers forever protection, inviolate and sacrosanct. The uncomfortable reality on the ground in the Amazon is that there is often a large disconnect between protected status in law and actual conferred protection. When land is appropriated from the traditional homelands of indigenous peoples to create parks under national control, paradoxically, it can often make the land more vulnerable to resource extraction. The laws of government may not be enforced, can be annulled, or simply rewritten with a new administration in response to powerful industry lobbying. Sometimes the extractive industry is the very driver behind the scenes to create a national park or other “protected” area. Despite public messaging to the contrary, indigenous communities are not fully consulted and as we found often surprised later to find out that areas of their lands have been taken away or use has been restricted. This is not very different to what has transpired in the United States, or for that matter in many countries of the world. This is why the mapping initiative and the capacitation was so important for the Matsés. We are grateful for the support of our funding partners that made this landmark initiative possible.

Voices of the Matsés: Video short on the Matsés Indigenous Mapping Initiative

Future Directions

Two Matsés youths from the community of Puerto Alegre leading the endangered river turtle program©Acaté

In this retrospective, we hoped to share some of the backstories of how Acaté developed as an organization, our work, and how we work. Even though this accounting is lengthy, it is still simply not possible to cover, even superficially, all the important programs including biodiversity assessment, sustainable agriculture, and many others, so we will highlight in brief a few:

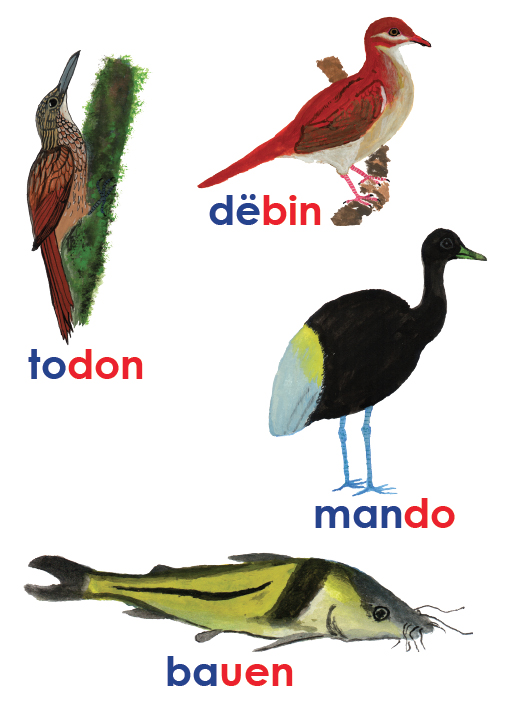

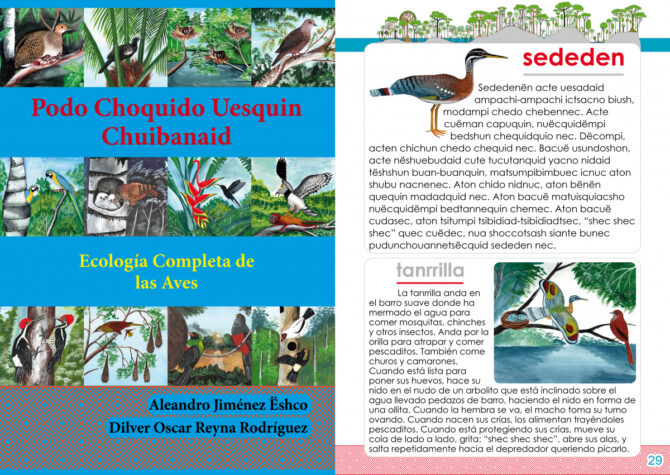

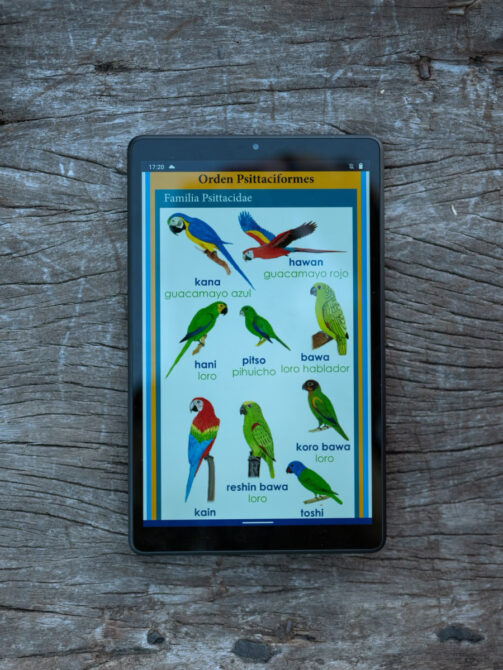

Bilingual education / Intergenerational transmission of ecological knowledge: To date, with Matsés authors and illustrators, Acaté has published 11 educational books, more than doubling the number of printed books written in the Matsés language, as well as developed 7 mobile applications that include lessons in the Matsés, Kokama, and Iskonawa languages, including the first cell phone app dictionary of an Amazonian language. The apps are downloadable here. In our future directions, we seek to find support for education programs, which at present moment is unfunded. For reasons that escape our understanding, there are relatively few grants available to apply for that support indigenous education.

Structured on an understanding of the components of Matsés language, Acaté published a Matsés elementary reader designed for accelerated learning. The reader can be used in both school and in the home; the latter is critical, particularly for smaller communities in which schools are inconsistently operational due to limited staffing. The animals, plants, artifacts and other elements of the local environment and of Matsés culture are painted by the Matsés artist Guillermo Nëcca Pëmen Mënquë. ©Acaté

Extract from the Advanced Introduction to the Ecology of Birds printed book (click here to download full pdf)©Acaté

A recent Washington Post article profiled the Iskonawa cell phone app. The Iskonawa are another Panoan group in the Peruvian Amazon who, unlike the Matsés, have only a handful of remaining native speakers. The Washington Post piece incorrectly credited the development of the app to another party; the app was developed by Dave and the Acaté team and is downloadable here. We were pleased to read in the article that the app has become “hugely popular” in the Iskonawa community.©Washington Post

COVID-19 pandemic: Acaté partnered closely with Matsés leadership to provide food and support for the Matsés during the dark and uncertain first months of the COVD-19 pandemic. Over a hundred Matsés were stranded in Iquitos without funds for food or housing due to one of the strictest enforced lockdowns imposed by any country.

Quarantine measures that limited hours of banks and other essential businesses paradoxically lead to larger gatherings, like this line here to a bank in Iquitos during the lockdown. For many, social distancing or staying at home was not an option. Most residents of Iquitos work for cash with little job security. Half of families do not have a refrigerator and had to venture out daily to crowded markets.©Acaté

The Peruvian Amazon, and Iquitos in particular, was one of the hardest hit regions in the world from the COVID pandemic. Shortages of even the most basic medical supplies and the deaths of dozens of healthcare personnel led to the closure of medical facilities in Iquitos or rendered them functionally inoperable. People who needed medical attention had nowhere to go and a black market was created overnight for medical supplies and oxygen bottles. International media reports, with headlines as “No Oxygen in the Lungs of the World” and images of morgues overflowing with bodies of victims wrapped in plastic bags, finally brought attention to the deep inadequacies and inequities of healthcare and other social support systems for Amazonian regions.

Coordinating distribution of food and cooking fuel for Matsés stranded in Iquitos during the early days of the pandemic©Acaté

©Acaté

Portrait of a Matsés family stranded in Iquitos during the early days of COVID-19 pandemic. Photographer Luis Adolpho. ©Acaté/Xapiri

Acaté helped to coordinate the extraordinarily complex multi-step evacuation of 80 Matsés safely back to their communities. Despite the Peruvian Amazon being regionally among the worst impacted in the world, not a single Matsés died of COVID during the pandemic.

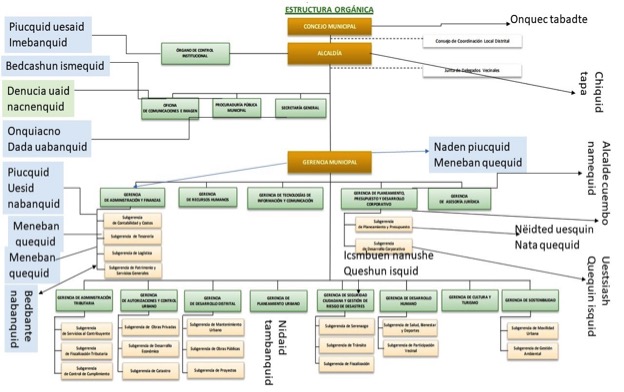

Governance and Territorial Protection: This has included building the aforementioned computer lab in Matsés territory, creative leadership training, development of life plans, translation of legal statutes into the Matsés language, territorial patrolling along their borders and protection of uncontacted tribes in isolation.

In 2019, Acaté and the Matsés launched the Governance and Leadership Initiative, and this year set up the first Matsés Women’s Association.©Acaté

In the course of Governance initiative, Matsés leaders created an organizational flow chart of the intended structure and function of the local government with Matsés explanations to properly access social services that Matsés communities are entitled to by the state, but often do not receive.©Acaté

©Acaté

In 2020, Acaté expanded our work to include the Kokama Native Community on the Marañon River. This reforestation project restored degraded land with a highly diversified assemblage of tree species, many of which provide non-timber forest products. The first harvests from this initiative will go to market this year, improving the livelihoods of the community.

As of writing, Acaté is deeply immersed in the launch of a major initiative to address food security, economic development, and women’s empowerment. This federation project is to create integrated aquaculture systems in all Matsés communities. This is one of our largest, most ambitious, and important initiatives to date. Please take a moment to read our recent field report on the progress of this endeavor. The reporting is representative of the depth and transparency that have come to characterize all of our field reports over the past ten years and remains unparalleled in the conservation world.

Fish farm in development. We look forward to the second year of advancing this high priority initiative.©Acaté

We wish to close this retrospective by thanking the many individuals and foundations who have believed in our work and supported us over the past decade. Thank you for being a part of Acaté. We are humbled by and grateful for your support and inspiration. For those reading this and just getting to know our work, please take a moment to learn more and consider supporting our projects. Acaté strives to be a vehicle of positive change in the heart of the Amazon rainforest. You can help can change the trajectory of a proud people struggling for their cultural survival amidst a profoundly shifting world. We operate with the highest level of transparency and impact, with minimal operating overhead.

Last but not least, we want to extend a special thanks to our partners, friends, and family who have supported us in this journey and to the Matsés indigenous people, whose partnership and friendship inspires our work daily.

With gratitude,

Chris Herndon and Bill Park

Co-Founders, Acaté Amazon Conservation