Acaté and the Matsés advance an extraordinary initiative designed to strengthen food security, climate resilience, women’s empowerment, economic development, medicinal agroforestry, and more!

The Acaté team and the Matsés have been hard at work advancing the second year of our integrated aquaculture (fish farms) project, last reported in our September 2023 Field Report. This initiative is one of our largest and most technically challenging projects to date, with far-reaching benefits.

We are pleased to report the successful development of over 30 integrated aquaculture systems of impressive scale in Matsés communities designed to enhance food security, reduce hunting pressures, create economic opportunities, and support a truly extraordinary medicinal agroforestry initiative. Each site integrates native fish production with agroforestry. The trees planted in the agroforestry areas serve four main functions. The first is nutrition for the Matsés, especially the children. The second is food for the frugivorous fish species. The third is the medicinal agroforestry component which provides both medicinal plants and training areas for apprentice traditional healers. The fourth is habitat and leaf-cone nesting sites over the water for the culturally and economically important kambo tree frogs.

By stacking functions in this manner, the Matsés are maximizing the use of the areas near their villages and enhancing its productivity. For example, the muck from the ponds increases the productivity of their staple crops planted near the ponds and increases the resilience to potential disturbances. For the Matsés communities, the direct benefits include enhanced food security, most importantly protein availability for children, increased economic opportunities, and easy access to plant medicines along with supporting a new generation of traditional healers. The indirect benefits include the recovery of fish stocks in the rivers, reduced hunting pressures on game species, and the reduction of the labor needed to meet their basic needs.

The project is immensely popular with the Matsés and has resulted in the establishment of the first Matsés Women’s Association, with active chapters in all nineteen Matsés communities. Matsés women are engaging in new community roles and governance, amplifying the voices of Matsés women in governance as never before.

Community-based fish farms are commonly undertaken projects for NGO and governmental agencies in the Peruvian Amazon. Examples, however, of successful community-based fish farm projects are hard to find. In addition to the multitude of on-site technical challenges that need to be overcome, failures result from poor implementation, inadequate cultural considerations and beneficiary engagement, and, particularly, from a lack of follow-through. The success of our initiative has reached the attention of several Peruvian governmental agencies, which have extended offers of collaboration. We have expanded the project to include the Kokáma indigenous people of the Marañón River, where the project leaders will help them replicate and adapt the project for their communities who face significant food security pressures and severe impacts of climate change.

For the Matsés, the goal for this coming year is to build a fish hatchery, centrally-located in the Matsés territory, to support the continued sustainability of the initiative. Acaté is working with an expert fish biologist to design and tailor its functionality to the remote setting of the Matsés territory. We are seeking funding to fully make this critical and exciting next stage a reality for the Matsés communities in 2025! To learn more about this exciting and impactful initiative, our full report follows below.

Background

The Amazon Basin holds one fifth of the world’s fresh water and harbors an extraordinary diversity of fish. Given the historical abundance and biomass of populations for many fish species, the need for fish farms in comparatively self-sufficient indigenous communities living along remote tributaries of the Amazon Rainforest may seem counterintuitive. Nearly all indigenous communities in the Amazon with sustained contact with the outside world have transitioned decades ago from traditional shifting settlement patterns to more fixed and permanent settlements that afford more access to infrastructure like schools and health outposts but creates real challenges for communities to meet dietary protein requirements. Global climate change, which is touching even the most remote regions of the world, has compounded the food insecurity through major shifts and unpredictability in rainfall patterns, challenging and bringing hardship to communities whose way of life and existence depends upon healthy forests and rivers.

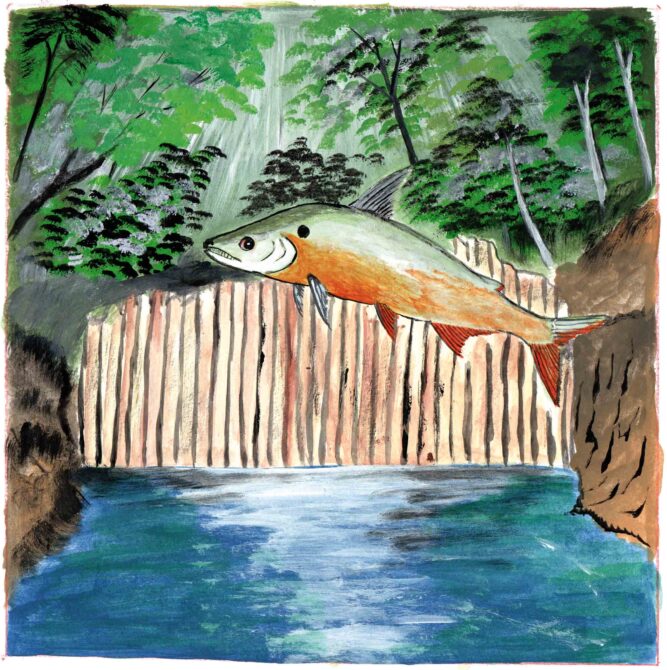

Traditional fishing weir, rendering by Matsés indigenous artist Guillermo Nëcca Pëmen Mënquë ©Acaté

Prior to first contact with missionaries in 1969, the Matsés moved their settlements every three years to a new locality where animal game was more abundant, allowing the rainforest to reclaim their farmland as well as for fish stocks in rivers to replenish. In this system, Matsés’ swidden agriculture, still practiced today, was superbly adapted to their former pre-contact semi-nomadic lifestyle. Steady access to abundant game balanced out the Matsés’ starch-rich, but protein-poor, polyculture. Major deficiencies and challenges, however, have arisen with their change to sedentary settlement pattern with fixed villages that support growing populations. These include:

1) Shortage of protein, for which children are most vulnerable and impacted.

2) Once fully-self sufficient, the Matsés are now increasingly drawn into the cash economy with the advent of the public education system, adoption of manufactured clothing, and the use of tin pots. All Matsés families today require a source of monetary income to support their daily lives. Outside of a small handful of village school teaching jobs, the sole opportunities to obtain it are by timber extraction or for the men to travel to cities in search of work.

3) Swidden farms inevitably being cut farther and farther away from villages. The Matsés require fuel, a significant cost to families, for their small outboard motor peque-peque canoes to efficiently access their farms positioned at distance from their village. Women are required to transport harvest increasingly longer distances as an inevitable consequence of swidden farms being cut farther and farther out.

4) With game animals increasingly distant from the permanent villages, men hike to hunting camps to smoke meat, and are absent from their village for 4-10 days. The women, then, are left in the villages with the responsibility of feeding their children, specifically through harvesting of swidden farm products, gathering wild fruits, and fishing. The latter requires a large investment of time, as the waterways along which most of the Matsés villages are located are small jungle streams with few and small fish. Fishing can become particularly challenging during the extremes of water levels in the rainy and dry seasons.

5) Last but not least, global climate change. Although the Matsés have not contributed to the drivers of global climate change, they tragically bear the impact of it. The Amazon region as a whole has been experiencing record draughts, stranding boats in large rivers, and killing fish. The smaller streams, called quebradas are now drying up completely and the larger streams where the Matses communities are located are being reduced to trickles during the low water period. While the average water levels have remained stable, extreme droughts and flooding periods have left the communities vulnerable.

The challenges faced by the Matsés are shared by many indigenous communities throughout the lowland Amazon Basin and highly relevant to conservation. It is critical to develop interventions such as this initiative to ensure food security and climate resiliency.

There are many examples of successful commercial aquaculture projects, including the export of fish for upscale restaurants around the world. Due to the pressing need and potential benefits, fish farms have also been community projects long advanced by conservation NGOs and governmental agencies in the Peruvian Amazon. Unfortunately the ground truth is that most community-based projects fail, not due to a lack of interest or commitment from the beneficiary community members, but due to poor implementation and particularly from lack of agency follow-through. In the case of Matsés, we are aware of at least five initiatives over the past two decades, the projects have ranging from blatant money-grab schemes from NGOs in which not a single action on the ground was taken, to a large scale well-funded initiative that resulted in construction of large building, now dilapidated, but no ongoing viable fish farms at the community level. In this backdrop, although Acaté has earned a reputation as an organization that can succeed in difficult projects through innovation and community engagement, even some of our partners were initially hesitant about launching a large scale fish farm project, aware that so many of these projects launched by other NGOs typically fail.

Fish farms have always been a high priority of the Matsés. The Matsés identified a large scale fish farm project as paramount for their food security and economic support and are highly motivated to support it. In response, in 2022, our organization made this initiative a multi-year operational priority. We, with the backing and encouragement of funding partners, are committed to providing the necessary support to successfully realize this vital project for Matsés food security, conservation, and economic development.

For detailed reporting on the first year and a deep dive about the construction of fish farms, please read our September 2023 Field Report.

Year 2 Report

Aquaculture systems are complex and many factors spanning numerous disciplines must be considered to achieve operational success. In the first year a technical specialist in fish farms trained Matsés project leaders, focusing on site selection and construction aspects. The Matsés are expert farmers so this training added on top of their already profound knowledge of their lands and soil types. Our focus in year two was to mature the fish farms built the prior year, further the training and capacitation of the communities, and to build additional aquaculture systems in the villages supporting the largest populations, such as along the Chobayacu Creek in the heart of their Ancestral Territory, which experience the most severe protein shortages and the problem of ever-increasing distances to the farming areas is most acute.

The changing climate has meant that the river levels are both higher and lower than historic extremes. This not only underscores the need for creation of fish farms for food security but also confers additional challenges in the construction. Some streams that were generally navigable year-round are now drying up completely during the low water season. To address this, we have been prepositioning materials in the communities upriver during the times of high water such that they’re available when needed. We have also taken advantage of the periods with limited rain to dig the ponds and tamp the clay down without having to deal with the thick mud. When the rain comes back is the ideal time for tree planting and makes for the highest survival rate of the seedlings and saplings. By adapting work schedules to the conditions, we have been able to overcome the challenges of the seasons and the changing climate.

To ensure the durability of the project in its second year we continued the training with the focus shifting to maintenance and problem solving. Aquaculture systems require a lot of maintenance in any climate and especially in the humid tropics where torrential rains are regular occurrences. These exceptional rains put a lot of stress on the dike systems and a good design is necessary to prevent overtopping of the dike. Periods of little rain and intense heat where the amount of water flowing out of the ponds and evaporating can exceed the amount coming into the pond. One of the key objectives was to ensure that the beneficiaries could maintain the ponds such that the water levels are stable. The water quality in the ponds must also be maintained for oxygen levels. By adding additional NPK fertilizer to the ponds the health of the microbial communities can be improved to maintain water clarity and oxygen levels.

The project beneficiaries being able to control water quality is another key component of successful maintenance. Training in dike maintenance and erosion control are additional important sub-components for the maintenance of water levels and water quality.

The maintenance and fish production training classes were carried out in all the villages by Acaté staff, and two expert fish biologists based in Iquitos. The training started with maintaining the levels of water in the ponds and making sure the pond is not overtopped during heavy rains. This involves cleaning out the tubes by removing all the accumulated organic matter. In addition, they assessed the areas where the terrain could lead to flooding and implemented measures to slow the water flow with swales or plantings. They worked on planting grass on the tops of the dikes to minimize damage should some overtopping occur. They also worked on solving the issues of low water in the ponds. This involved cleaning and maintaining the springs of wells that feed the ponds and checking for seepage or leaks in the dikes.

The advantage of having multiple ponds in each community is the ability to remove the fish from a pond for maintenance. This can be required if some water channels form under the compacted clay dramatically lowering the water level or if the pond must be made deeper and re-compacted. One of the innovations that the Matsés started employing is the use of palm wood steaks to control erosion by pounding the stakes, which resist rot, into the border of the ponds to stabilize the banks with the tops of the stakes catching the sediment. This really helps keep the water clean while the plantings grow.

Water quality in the ponds is critical to successful fish production with low water oxygen being the most common problem. One common solution is to add aquatic plants to the pond and certain plants can also help with water quality by adding the fresh leaves. Pond mucking is the most well-known maintenance chore and is key to avoid the buildup of decomposing organic material that can deprive the pond of oxygen the fish need. The Matsés communities will mature the muck to use it as a fertilizer for the associated agroforestry sites to supplement the nitrogen-poor “soils” of the Amazon.

The care and feeding of the fish were one of the top priorities for the training. For each pond constructed Acaté provided a scale to weigh the fish food and a hand cranked mill to grind corn. The fish have different nutritional requirements during their growth cycle, with higher protein required during the first months, and then a higher percentage of fruits and vegetative matter as they grow. One innovation mentioned earlier is pounding palm wood stakes into the ponds separated by a fixed amount to create pens for fish of a certain size. The fish have different dietary needs during their growth cycles and providing them with less-than-optimal amounts of food will slow their growth while overfeeding is both wasteful and can adversely affect water quality.

One of the major advances in year 2 has been increased production of fish food on the community level. We initially started the feeding program with commercial balanced fish food to ensure sufficient protein. The training showed the beneficiaries how to capture and weigh the fish to calculate the amount of food and the nutritional balance of the food depending on the age of the fish. The Matsés developed and transitioned from commercial fish food to their own protocols for fish food utilizing a diversity of available nutrient sources. For example, the forests adjoining the integrated aquaculture sites have an abundance of ant and termite nests. The Matsés have been using these nests as protein-rich food source for the fish fry in the stage where they require high levels of protein.  The creation of a balanced fish food from the Matsés kitchen scraps has been another major advance. The areas around the villages where the Matsés can grow corn are limited and the Matsés value the mashed corn drink chicha. While the beneficiaries are willing to invest some of their corn crop as fish food, it is much better to develop sources of fish food from kitchen scraps and waste products. By using cassava, something they have in abundance along with fruit seeds, the Matsés have been able to make excellent fish food using waste streams. This mix can be sun dried and pelleted for storage when the palms are in season.

The creation of a balanced fish food from the Matsés kitchen scraps has been another major advance. The areas around the villages where the Matsés can grow corn are limited and the Matsés value the mashed corn drink chicha. While the beneficiaries are willing to invest some of their corn crop as fish food, it is much better to develop sources of fish food from kitchen scraps and waste products. By using cassava, something they have in abundance along with fruit seeds, the Matsés have been able to make excellent fish food using waste streams. This mix can be sun dried and pelleted for storage when the palms are in season.

In another year the trees planted around the ponds will start producing, especially the macambo (Theobroma bicolor) making the feeding much easier. Another innovation has been the use of palm seeds, different types are available year round, and include aguaje (Mauritia flexuosa) and ungurahui palms (Oenocarpus bataua). The seeds are large and very hard making them impossible for small fish to consume but the Matsés are using their large wooden grain crushing basins to pulverize these seeds to create a commercial fish food equivalent. These palm fruits are an important part of their diets, and the seeds are normally discarded. The food can be dried and stored for future use. As a note there are palm fruits that have suitable seeds available year-round. The Matsés grow a lot of sweet potatoes but one of the downsides of having sweet potatoes growing near the homes is that the sweet potatoes attract spiny rats that in turn attract venomous snakes such as the common jergon (fer-de-lance). The sweet potato leaves make excellent fish food and are readily gobbled up by the fish, and clearing the leaves helps prevent snake bites. This is an excellent use of the leaves when the Matsés clear out the sweet potatoes which grow like weeds near their homes.

For each community, at the end of the training period all of the fish farms were verified as structurally sound and the beneficiaries fully trained in all relevant techniques for success. As of writing, over 30 (and counting) integrated aquaculture sites have been created. The ponds created in year one are now producing fish of harvestable size!

Matsés Women’s Association

The aquaculture project was operationally paired in the formation of the first Matsés Women’s Association, which, along with other critically important governance, empowerment and economic functions, are in charge of the long-term maintenance of the fish farms. Many young Matsés mothers joined this association because they are concerned about future food security and the availability of protein for their children. They are committed to create economic opportunities for their families that don’t involve work in the dangerous, back-breaking, and poorly-paid timber cutting industry or where men have to be away from their communities for prolonged periods of time.

Women are underrepresented in Matsés tribal leadership in general and women’s issues are too often de-emphasized during meetings. There was considerable excitement among the Matsés women for the creation of this association. Reservations were initially expressed by some women on the effectiveness of this association. In the past, various NGOs and agencies had received international funding to set-up women’s empowerment projects and workshops. The projects never materialized and the workshops turned out to be effectively one off photo-ops where one or two Matsés women traveled to the cities of Lima or Iquitos for a day. In one workshop held in Lima, translation services were not provided even though the selected Matsés woman representative was not a primary Spanish speaker. Fortunately, initial doubts changed to enthusiasm as the practical nature of the Matsés Women’s Association became apparent, the role of Matsés women in leading it and shaping its direction, and the role of the association in coordinating the sustainable economy program.

The approach was not to create an organization top down with one governing board for the entire Matsés population, but to establish, one at a time, chapters in each village. The women’s association’s role in the Matsés community was then codified in the native community governance and the CCNN Matsés now has chapters of the Women’s Association in all nineteen villages. These chapters are led by a president and a three-member board selected in an election in each village and approved by the general assembly of the village. The Matsés Women’s Association began participation in our sustainable economic programs.

The formation of a Matsés Women’s Association has allowed Acaté to work directly with the women’s association to manage the traditional crafts project. They equitably distribute the sales to their membership and deliver quality-controlled items to our staff. In addition, the sustainable economy program has already yielded a significant order generating income for the membership.

The Matsés Women’s Association has amplified the voice of women in the community. With each village having its own Women’s Association the women can be better organized and form a consensus among their membership with regards to issues of community life.

Due to the increased organization of the village level, we are now seeing more women who are delegates to the general assembly (the maximum authority a native community where legally binding decisions are made). In the last assembly meeting in July the new leadership of the Women’s associations and the local chapters were all recognized, and it was agreed that the role and representation of women should be increased. For example, all the Matsés agree that it is a good idea for women to train as traditional healers with the remaining elder healers. Women now take at least half of the places in the traditional medicine courses and hopefully seek training to become health promoters for their community!

Medicinal Agroforestry

In addition to the new aquaculture systems, we incorporated medicinal agroforestry plantings or “Healing Forests” to the areas around the existing ponds. The goal of medicinal agroforestry is to train young Matsés in the use of their ancestral medicinal knowledge and to plant medicinal trees, vines, and epiphytes. This design methodology adds nested functionality or what in permaculture is called “stacking functions”. This increases the productivity of the area and adds efficiency.

In each site between 1500 and 2000 trees are being planted. The diversity of trees, vines, and epiphytes planted is unprecedented and would stand alone be an extremely impressive reforestation project by any measure.

The Matsés carefully select and transplant many of the trees as saplings from the surrounding forests. These saplings, generally growing in the shade of a larger tree, can be many years old. Over the years these saplings have developed defenses and root structures to survive in the shade while waiting for an opening in the canopy and additional light to allow them to grow rapidly. This technique markedly increases the success rate of the plantings, simply planting seeds for many species in sun-exposed open areas of eroded soils will not work.

The subject of the Matsés’ traditional knowledge of medicinal plants is immense and beyond the scope of this report. For each integrated aquaculture system built there are six Matsés apprentices trained including at least three women receiving training from the elders in the use of the Matsés traditional medicine.

The apprentices are a mix of the best students from previous training sessions and new students as determined by the elders. In addition to the six official participants in each village there have been volunteers who are auditing the course. Some of the apprentices that started in the program eight years ago are now teaching others the medicines that they know.

Next steps

As a result of this initiative, forty Matsés, who previously had little or no experience with fish farms, are now experts and highly proficient in building fish farms. The integrated aquaculture program this fall is being expanded to the Kukama-Kukamiria communities on the Marañón River. Matsés project leaders are now training the Kukama-Kukamiria! This interchange of knowledge and training is a key component in building real and effective federations to represent indigenous people. In addition, many Matsés learned how to build fish farms and by their own initiative are building additional integrated aquaculture systems in their communities. Over time, we expect that the number of sites built outside of the project will exceed the number built during the project.

The government of the District of Yaquerana has taken notice of the success of the project and offered logistical support with their boats to deliver fish fry. The Director of the Matsés National Reserve (SERNAP) is also impressed by the project and pledged to help some villages with fish stocking and use the project as a model for other river basins outside the Matsés Ancestral Territory.

A major remaining challenge has been supplying fish fry to the remote sites via chartered airfreight. Currently the fish must be brought from Iquitos by chartered float plane. These flights are irregular at best and the costs are not sustainable. The fish fry in the transport boxes have oxygen for eighteen hours, after this period the mortality of the fish expands rapidly. The fish packing begins at 2 am then the transport to the airport from the fish facility outside of Iquitos takes two hours. The health inspections can take another two hours. Then there are the flight delays. To date we have been lucky with our planning but as the number of aquaculture systems increases along with the demand for fish fry using air freight will become increasingly impractical.

To address this challenge, for the coming year we plan to build a simple, yet practical, fish production area in the Matsés territory centrally located that will provide fish fry of three different species in appropriate quantities to supply all the communities. When people think of a fish laboratory they might imagine an elaborate building filled with stainless steel contraptions and enormous tanks. This is not requisite or appropriate to remote and resource-constrained settings. In reality the most important element of fish production is having sufficient pond area for each species and to segregate different age fish.

The first step of this project will be building six ponds, two for each of the species. Acaté has identified an ideal site centrally located near the banks of Javari River to build the ponds and the breeding facility. This location, centrally located to all three river systems of the Matsés territory, will make it easier to bring the concrete for the slab, the fiberglass tanks, and the pipes from Iquitos. These ponds will include many of the same features as the over 30 ponds built in the course of the project such as protected areas for the fish to hide from avian predators and associated tree plantings to provide the right amount of shade. The work of building ponds has already started!

Aquaculture sites are built on eroded, deforested areas near the villages©Acaté

The scale of the aquaculture farms is impressive. The construction is accomplished without use of earthmovers or mechanization.©Acaté

Newly created aquaculture site maturing. Soon fish will be added in stages. ©Acaté

Fish larvae are very sensitive to water conditions and have very specific feeding requirements. The larvae will be grown in simple fiberglass tanks where the water is filtered and aerated to optimal conditions for the fish.

As the larvae grow they can be released into the outdoor ponds to continue their growth cycle until they are of the optimal size for transport to the beneficiaries. There are very specific procedures for the gravid females and collection of male gametes that will be included in the training for the Matsés. Over the last year we developed an effective fish ladder protocol to move the fish up river to the most distant Matsés communities. We have been creating custom holding pens using mosquito netting and moving the fish by boat at night for a maximum of eight hours. Then the fish are placed in the custom built pen and allowed to rest and feed until they are moved to the next stop. Even the most remote village only requires two or three stops depending on the water level. We will continue with this method only without the difficult air freight journey the logistics and timing will be much better. Over the course of the coming year we will continue to add and improve the medicinal agroforestry sites adjacent to the aquaculture sites built in year two as well as other maintenance activities and addition of trees and crops will continue in year three as needed to ensure maximum productivity from the sites.

We are grateful for our funders whose support and vision made this extraordinary work possible and look forward to realizing the full potential in the coming year!

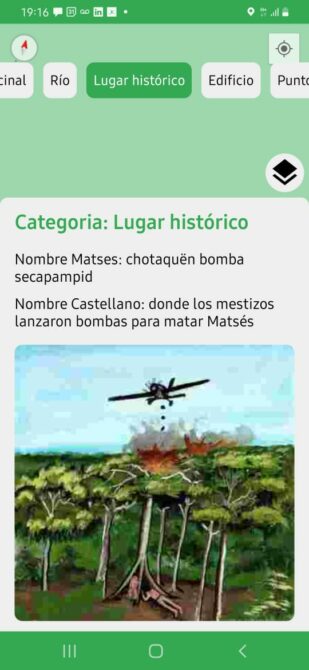

If you missed it, take a look at our July 2024 field report on the launch of a pioneering mobile application built from the ground up for territorial protection and preservation of ancestral knowledge!

Georeferenced historical site of a Matsés communal longhouse bombed by the Peruvian military during the 1964 Requena-Yaquerana expeditions. The app is downloadable here at the Google Play Store.©Acaté

Matsés leaders and Acaté staff presenting the app at a recent assemblea (meeting) of representatives from all the Matsés communities in Peru.©Acaté

Also, Acaté was recently featured on CNN International and CNN Espanol, and CNN Espanol series Ancestral Guardians!

Acaté Amazon Conservation is a non-profit organization based in the United States and Perú that operates in a true and transparent partnership with the Matsés people of the Peruvian Amazon to maintain their self-sufficiency and way of life. The Matsés safeguard a critical conservation corridor and shield some of the last remaining uncontacted tribes in isolation from unwanted encroachment from the outside world. Acaté works to protect their forests and way of life through supporting on-the-ground initiatives that are led by the Matsés indigenous people.

Operating on the frontlines of conservation, Acaté’s initiatives over the past decade have included the first indigenous medicine encyclopedia as well as projects with original methodology in sustainable economic development, traditional medicine, medicinal agroforestry, nutritional diversity, regenerative agriculture, integrated aquaculture systems, biodiversity inventory, education, native language literacy, participatory mapping, and protection of uncontacted tribal groups in isolation. All of our initiatives are developed with, led and implemented by the Matsés indigenous people. Donations are tax-deductible and go directly to fund these on-the-ground initiatives that operate with unparalleled transparency.

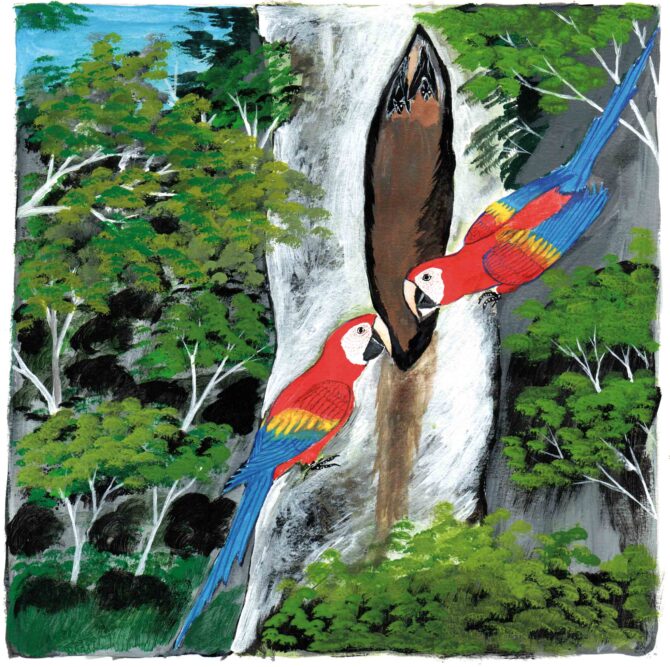

Acaté recently shared nearly 700 exquisite watercolor paintings by Matsés artist Guillermo Nëcca Pëmen Mënquë showcasing the incredible biodiversity of the Amazon Rainforest! Take a moment to view Guillermo’s extraordinary work in the Matsés Rainforest gallery. Here, a Scarlet Macaw (Ara macao) gnaws along the edges of tree holes when it smells bat urine to collect minerals. ©Acaté

All content and images copyright 2024 Acaté