Cultural Preservation through Literacy

The fate of a culture is inseparably bound to its language. The present state of native language education in most indigenous groups of the Amazon is deeply problematic. Although access to bilingual education is recognized by national governments as a fundamental right of indigenous peoples, the challenges to the development and successful implementation of such educational programs are multifold. Smaller indigenous groups and communities with less external resources face the greatest challenges. In his latest field report, Acaté Field Coordinator Dr. David Fleck reports on the publication of an innovative reader he developed to provide a tool for Matsés families to impart literacy in their native language to their children.

Bilingual education, in the context of indigenous people like the Matsés, whose children are essentially monolingual speakers, entails teaching in the native language in preschool and primary school. In addition to the pedagogical advantages of teaching reading, writing, arithmetic, etc. in a language that the children understand well, bilingual education also plays a very important role in the intergenerational transmission of traditional knowledge, raising the status of the language and culture, and elevating the self-esteem of the students.

The Peruvian constitution recognizes the rights of indigenous peoples to express themselves and to learn in their native languages. Indeed, the Ministry of Education has commendable policies for providing bilingual education to speakers of the 47 indigenous languages spoken in Perú. Unfortunately, the barriers to carrying out or implementing these policies effectively with each indigenous group are considerable. With few exceptions, it is not possible to state honestly that bilingual education in Perú has hitherto been a success. However strong the national mandate, the success or failure of transmitting literacy depends entirely on efforts at the local level. In general, the smaller the ethnic group the greater the failure. In the case of the Matsés, the Peruvian Ministry of Education has not published any pedagogical materials or books in the Matsés language except for four workbooks published in 2006 that were so poorly written that they are unintelligible for Matsés teachers.

Blue-crowned motmot (Momotus momota) as rendered by Matsés artist Guillermo Nëcca Pëmen Mënquë©Acaté

Summer Institute of Linguistics (SIL) missionaries, who used to be in charge of Matsés bilingual education in the 1970s and 1980s (and contributed to Matsés education up to 2001), produced a fine series of readers and math books and a few collections of myths and other narratives. Other than their translation of the New Testament, there are no copies of SIL publications remaining today in Matsés communities. In addition to the lack of pedagogical materials and books written in the Matsés language, poor training of Matsés schoolteachers, frequently cancelled classes, multi-grade classrooms (where teachers have to instruct students in up six different grades at once), and a multitude of other resource and cultural challenges have contributed to the low quality of education that the Matsés receive.

We have already made several contributions to the stock of reading materials in the Matsés language. Acaté has produced a 500-page encyclopedia of medicinal plants entirely written by the Matsés in the Matsés language, and a second volume of the Encyclopedia will be ready in a couple months. With the collaboration of several Matsés authors, I have produced a dictionary, a book of their traditional life, an extensive history book, and two short readers. However, other than the readers, these books are meant for adults, so there is a special need for children´s literature that will motivate parents (and older brothers and sisters) to read with their children at home and to teach them to read in their own language.

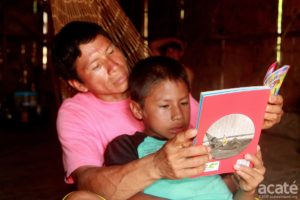

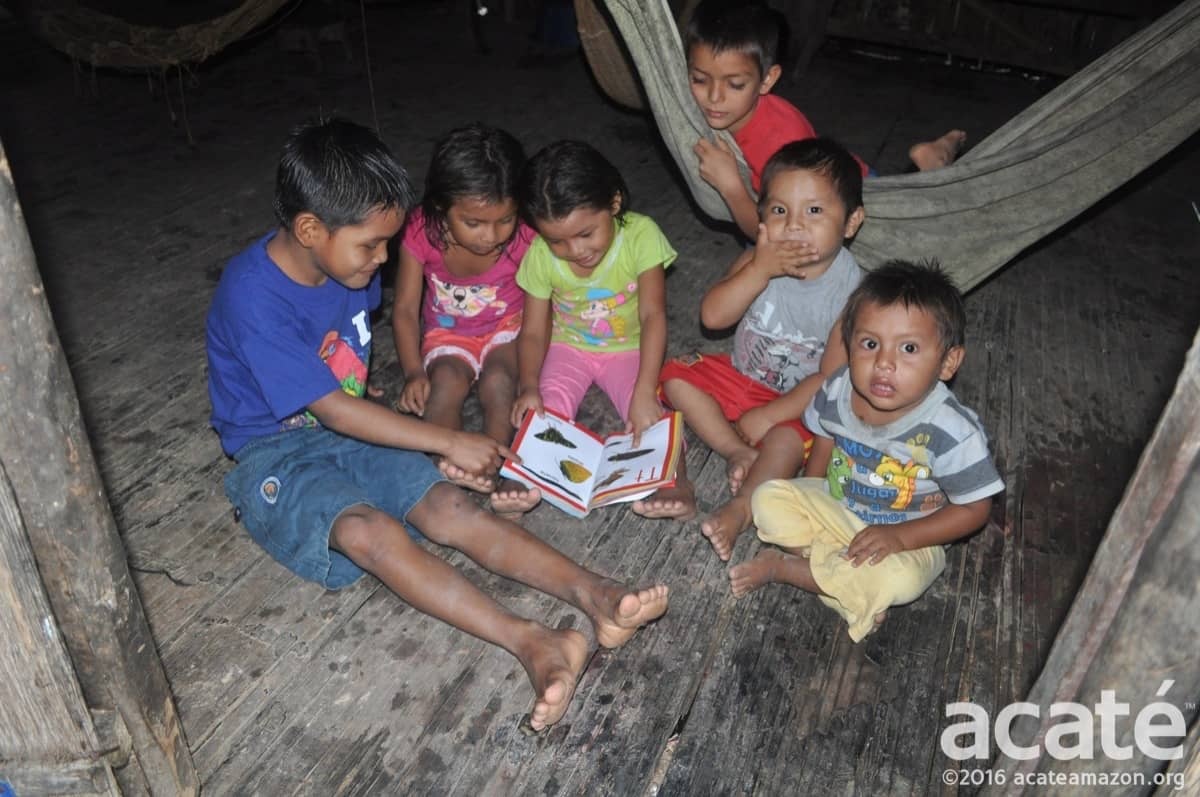

Success or failure of transmitting literacy depends on efforts at the local level.©Acaté

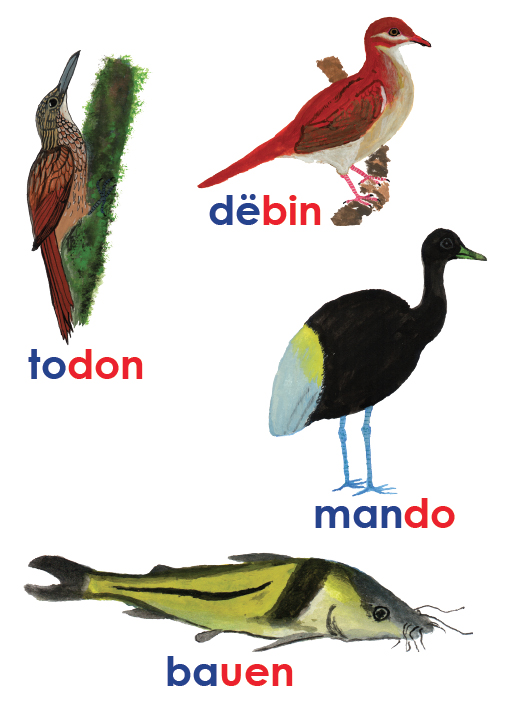

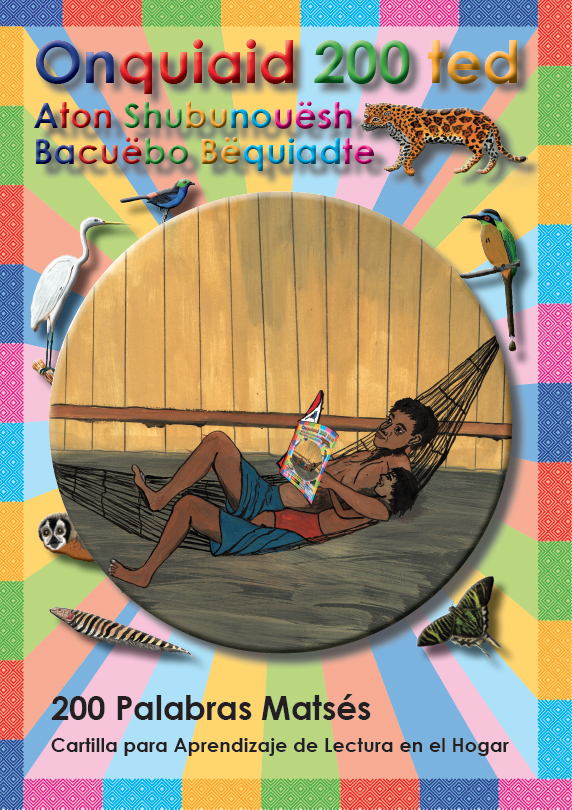

Acaté is proud to announce the publication of a reader entitled: Onquiaid 200 ted: Aton Shubunouësh Bacuëbo Bëquiadte (200 Matses Words: A Reader for Learning at Home). This 146-page reader includes 200 original watercolor illustrations of animals, plants, artifacts and other elements of the local environment and of Matsés culture painted by the Matsés artist Guillermo Nëcca Pëmen Mënquë. The reader was written by me based on my understanding of the structural properties of the language, my experience as a substitute teacher at the primary school at the Matsés village of Estirón (where I live), and my experiments teaching my son, nieces and nephews to read in Matsés.

The Matsés language is a member of the Panoan language family that is centered in eastern Perú, western Brazil and northern Bolivia. There are 32 known Panoan languages, although it is suspected that the uncontacted tribal groups in isolation near the Matsés territory are also Panoan-speaking. Of the 32 historically recorded Panoan languages, only about 18 are spoken today and, of these, 6 are no longer spoken as the everyday language. Although the Matsés language contains structural components shared with related Panoan languages, the Matsés language has several unique and very interesting aspects, including one of the most intricate evidential systems ever described for any language, requiring a speaker to precisely and explicitly code their source of information every time a past event is reported. In other words, the suffix of a verb changes depending on the certainty of the source of reported information; there are suffixes marking reporting that is experiential (direct experience), inferential (inferred from evidence resulting from an event), or conjectured (speculation without concrete evidence). Another unique construct of the Matsés language is what I refer to as the ‘double tense’ in which different verb suffixes are applied both to indicate the relative timing of past event being reported and the duration from its observation to when it is being reported.

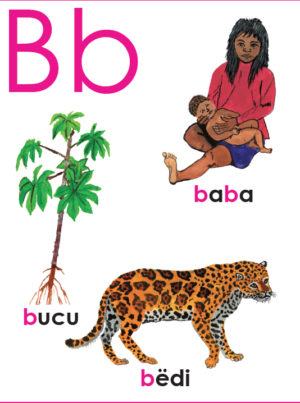

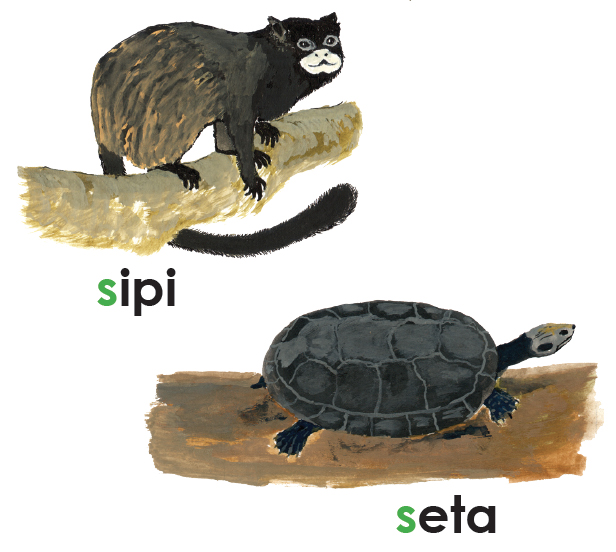

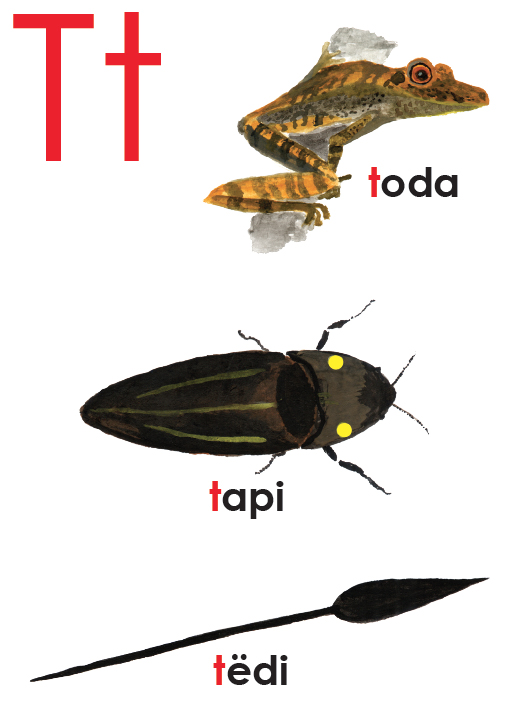

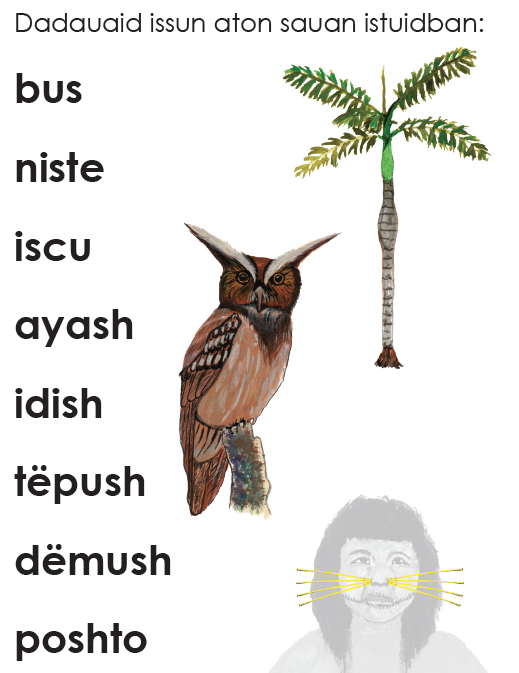

In the first half of the reader, each letter in the Matsés alphabet is introduced in turn, starting with the 6 vowels and followed by the 15 consonants. Each letter is introduced in a pair of facing pages, where 5 or 6 words written with the letter of interest are presented directly beneath a drawing illustrating the word. The drawings represent entities that the Matsés children will readily recognize (local flora, fauna, farm crops, and artifacts), and the words selected are as short as possible. This page allows the child to associate illustrated concepts with their written representations, and to become familiar with the pronunciation of the introduced letters. The following pair of facing pages are the test pages: they contain the exact same words and drawings, but the words are written in a column to the left, away from the drawing, requiring the child to be able to read at least part of the words to know which drawing they represent. The second half of the books is similar in structure to the first half, but rather than introducing letters, different syllable types are introduced. Words with few simple syllables are introduced first, then words containing many simple syllable, then short words containing complex syllables, and so on. Diagraphs (single sounds represented by two letters), such as ch and sh, are more difficult to learn and therefore introduced later in the book, and avoided as much as possible in words in the beginning of the book.

The reader includes 200 original watercolor illustrations by Matsés artist Guillermo Nëcca Pëmen Mënquë of rainforest animals and cultural artifacts familiar to the Matsés.©Acaté

Structured on an understanding of the components of Matsés language, the reader is designed for accelerated learning. The reader can be used in both school and in the home; the latter is critical, particularly for smaller communities in which schools are inconsistently operational due to limited staffing.©Acaté

The Matsés language has fifteen consonants and six vowels. A word-level alternating rhythmic stress pattern characterizes the sound of the language.©Acaté

The reader includes practice exercises to reinforce home learning.©Acaté

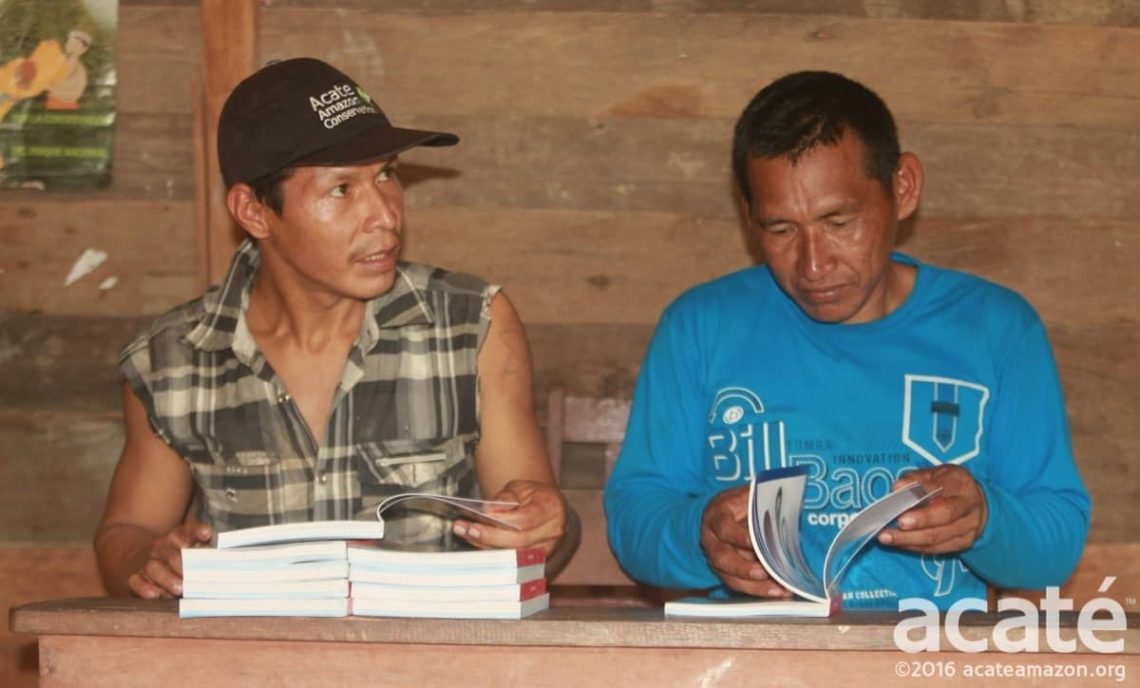

Distributing the reader at a community meeting©Acaté

In November 2016, with the coordination of Matsés leaders, Acaté distributed 500 copies of the reader to families in all 14 Matses villages in Perú. The reader was printed in full color on glossy heavyweight paper with durable binding, to ensure that the books last. Copies were given to parents who had children in kindergarten or the first years of primary school, with instructions on how to use the reader to teach their children to read. The reader was enthusiastically received in all the Matsés villages! Both children and adults alike immediately took much interest in the book as soon as they received them, attracted by Guillermo Nëcca´s life-like and vivid illustrations. This high level of interest and engagement is essential, since no matter how effective the teaching strategy of the book is, it will not be successful unless children and parents spend much time with it. We have high hopes that this reader will make a significant impact in Matsés children’s ability to learn to read and write in their language.

As it has only been a short time since it was distributed, we can only provide here in this report some preliminary experiences and observations. The kindergarten teacher in my village asks her students to bring their copies of the reader to class so she can use it to teach them. Guillermo Nëcca and I used printed test versions of the reader to teach their young sons and nieces and nephews to read, and were successful in doing so in less than two months. This is significant because most Matsés children are currently acquiring the ability to read only in the third or fourth grades. We have observed in the past weeks many children are spending time looking at the book trying to read the words, and asking their parents daily to teach them to read the book with them. One very pleasant surprise is that older children have been using the reader to teach younger children how to read. When the children play outside in mixed age groups, the older children are gathering the younger ones and playing teacher by having the younger children read from the book. This game is so popular among the children that some of the children who were playing students in one group are now finding other children to play teacher with them.

In May, Acaté will hold its yearly meeting with the Matsés leaders (including the chiefs of all 14 villages), where we will ask them to give us feedback on the success of the readers. In few months we will provide another update to let our readers know what the Matsés say about the effectiveness of the book.

To view the full reader:

Onquiaid 200 ted: Aton Shubunouësh Bacuëbo Bëquiadte (200 Palabras Matsés: Cartilla para Aprendizaje de Lectura en el Hogar) Grupo Tabano SAC Iquitos 2016 ISBN: 978-612-47280-0-6

Acaté field coordinator and linguist Dr. David Fleck is a fully integrated member of the Matsés community and lives with his wife and two sons in one of the most remote villages. In addition to over 30 scientific publications, Dave has co-authored with the Matsés an authoritative book on their culture, the most comprehensive dictionary of the Matsés language, the first written history of the tribe as told by elder Matsés historian Manuel Tumí, as well as educational materials in the Matsés language for their primary schools.

Dave with family in Estirón©Acaté

Acaté is an on-the-ground conservation organization that works directly in a true and transparent partnership with the Matsés indigenous people to maintain their self-sufficiency and way of life. The Matsés safeguard one of the great areas of rainforest on the planet, protecting a region of over 3 million acres in Perú alone and shielding some of the last remaining uncontacted tribes in voluntary isolation from unwanted encroachment from the outside world. Donations are tax-deductible and go directly to fund these on-the-ground initiatives that operate at the leading edge of conservation with unparalleled transparency. Stay tuned for further updates on our work. If you missed it, take a look at our December field update announcing the launch of two exciting new initiatives, the Matsés Comprehensive Herpetological Inventory and the Uitsun Traditional Handicraft Project!