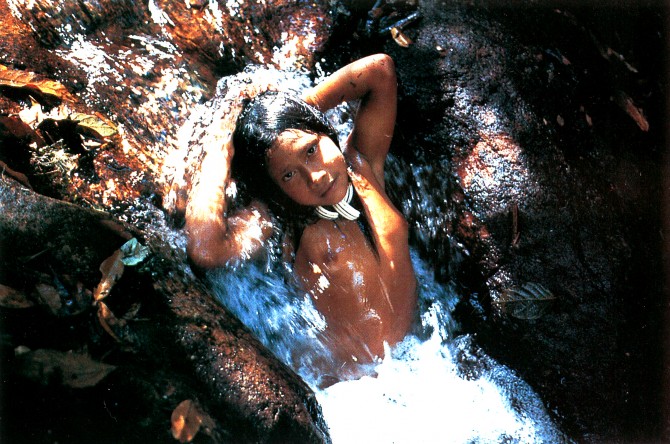

Urueu-Wau-Wau hunter in a quebrada Photo: L. McIntyre

Many of us recognize some of the more famous tribes of the Amazon, such as the Yanomamö and Kayapó, have seen their images and heard their voices.

This is the second in a series of posts by Acaté bringing to light a few of the dozens of unheralded tribes that have disappeared in the past half century or struggle precariously today on the margin of extinction.

The year was 1986. National Geographic photographer Jesco von Puttkamer was on assignment deep in the frontier of Western Brazil to take pictures of a recently contacted tribe, known as the Urueu-Wau-Wau, that had emerged from the forest. Among the images he captured were striking photographs of tribesmen engaged in the hunt with bows and arrows. Tapirs, large mammals of the forest, were bleeding to death, lying in pools of blood.

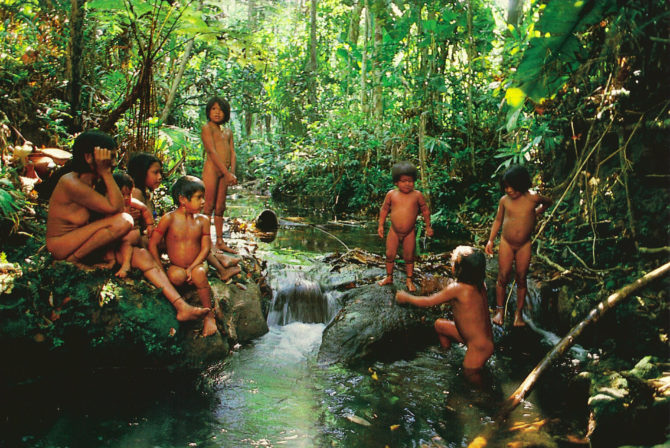

Urueu-Wau-Wau children at play in a forest stream. Photo: L. McIntyre

Few outsiders had as much experience with Amazonian tribes as von Puttkamer. He recognized immediately that the Urueu-Wau-Wau arrow poison was something novel. Amazonian curares kill through paralysis of muscle, hence their adoption into medicine that revolutionized the practice of surgery. But these animals were bleeding out, not dying through suffocation. Most Amazonian arrow poisons are extracted from jungle vines or lianas. Yet, the poison coating the tips of Urueu-Wau-Wau arrows came from the blood-red resin of a tall tree.

Puttkamer’s photos of Urueu-Wau-Wau and their arrow poison were featured in a 1988 National Geographic Magazine piece entitled “Last Days of Eden: Rondônia’s Urueu-Wau-Wau Indians”. The arrow poison caught the attention of Merck Pharmaceuticals, who arranged for additional material to be collected and sent to their New Jersey laboratories. Blood thinners or anticoagulants are big business. Today, the global market share for anticoagulants exceeds 9 billion dollars, the United States accounting for over 60% of that market.

Experts at the New York Botanical Garden were able to identify the tree as Cariniana domestica, a member of the Brazil nut tree family. Although C. domestica was first described by botanists in the early 19th century, it was not considered remarkable, just another Amazonian tree. In fact, the entire Brazil nut plant family was generally regarded to be chemically inert and not thought to harbor potentially valuable pharmaceuticals.

Arrow tips being coated with the toxic red sap squeezed from the stringy bark of the tike uba tree Photo: von Puttkamer/National Geographic

At Merck laboratories, the active principle was isolated from collected material and determined to be a potent anticoagulant inhibiting the thrombin, the basic protein of blood clots. When scientists from Merck published their findings, the tribe was not credited by name, the arrow poison was cited ‘used by the native individuals of Rondônia, Brazil’. In the acknowledgements, multiple contributors were credited but not a single indigenous person.

A midwife helps young Urueu-Wau-Wau mother anoint her newborn son with red urucum to ensure health and vigor. Photo: von Puttkamer/National Geographic

For Acaté’s conservation partners, the Matsés people of the Peruvian Amazon, it is a story all too familiar.

Our health has always depended on the natural world. Since the dawn of history, mankind has relied on plants, animals, and microbes to alleviate suffering and disease. The lesson of the tike uba poison and the monkey tree frog is clear: it’s not about what we know, it’s about what we don’t know. What are we losing with each hectare of rainforest that is burned? © Acaté

This frog holds a secret. Locked within its skin secretions are several novel peptides with narcotic, antibiotic, and vasoactive properties that hold much promise in medicine. Although the giant monkey tree frog (Phyllomedusa bicolor) has been known to naturalists for centuries, this secret was only recently revealed to the outside world when the Matsés tribe was first encountered deep in the Peruvian Amazon.

The Matsés know the frog as acaté and have long used its potent skin secretions in hunting rituals. For the Matsés, ceremonial use of acaté confers not only strength and courage to an individual but is a medium for transmission of knowledge among participants. For these reasons, we adopted Acaté as the name for our organization in recognition of the wisdom of our conservation partners, the Matsés people.

After reports of its use emerged from the forest, investigations of the frog’s secretions in the laboratory revealed a complex cocktail of peptides with potent vasoactive, narcotic, and antimicrobial properties. Several pharmaceutical companies and universities filed patents on the peptides without recognition of indigenous peoples for which it has long held a unique and important role in their culture. The gene for one of the frog’s antibiotic peptides has even been transgenetically placed into the potato plant to enhance resistance to pathogens.

The eminent Yale anthropologist Weston La Barre, who worked with indigenous peoples in Colombia, wrote:

As scientists, we cannot afford the luxury of an ethnocentric snobbery which assumes that primitive cultures have nothing whatsoever to contribute to civilization. Our civilization is, in fact, a compendium of such borrowings. Indeed, a good case could probably be made that, in the long run, it is the ‘higher’ culture which benefits, the more thoroughly being enriched, while the ‘lower’ culture not uncommonly disappears entirely as a result of the contact.

In a few short years, the life of the Urueu-Wau-Wau would be shattered by contact with the outside world.

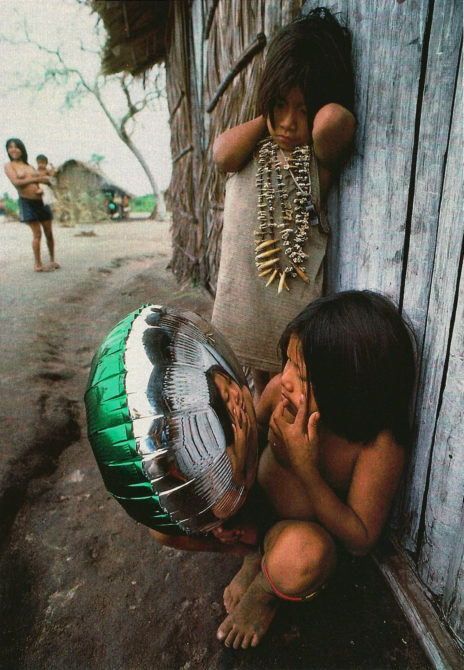

Photo: L. McIntyre

In the decade that followed contact, most of Urueu-Wau-Wau population was killed off as a result of conflicts and a series of respiratory diseases that struck their villages. Today, only 115 remain. The Urueu-Wau-Wau, who refer to themselves as the Jupaú, have done much to regain their identity and footing. However, as is the case for many tribes, much of traditional knowledge of the elders was lost in the waves of disease and through the impact of missionary activities. The vast territory of Rondônia was overrun in a massive gold rush. Today, the region maintains the highest rates of deforestation in Brazil as well as continues to be plagued by violent conflicts between indigenous peoples and land grabbers, diamond prospectors, and cattle ranchers.

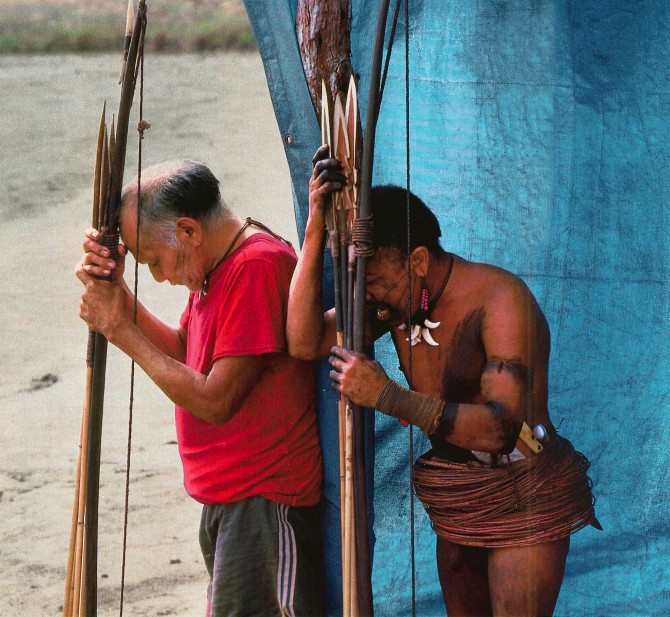

Urueu-Wau-Wau chieftan and younger warrior debating what do do about intruders on their territory. Photo: von Puttkamer/National Geographic

The once pristine forests of Rondônia today have the highest rates of deforestation in Brazil. Photo: von Puttkamer/National Geographic

Each tribe is part of the tapestry of humanity. Acaté works with some of the remaining tribes in the forest – living on the knife-edge and struggling for their cultural survival amidst a profoundly shifting world – to return control of their cultural and environmental destiny back into their hands where it once belonged.

Please consider donating today and help the guardians of the rainforest protect the living heart of our planet, for all of us.

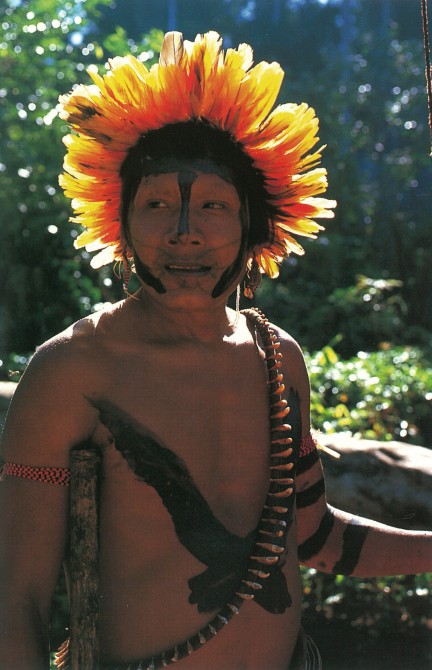

In Urueu-Wau-Wau cosmology, the sun is a benevolent being whereas the moon is a wasteland populated by nightmares that fall down upon the earth. L. McIntyre

The macaw is the sacred totem animal of the Urueu-Wau-Wau, whom believe they are descendants of the resplendent bird. The characteristic facial tattoos of the tribesmen represent the circular three facial lines of the blue-and-yellow macaw. Photo: L. McIntyre

The process of acculturation transforms once proud cultures into fragmented remnants, their self-sufficiency and social cohesion stripped away, leaving younger generations to struggle and reclaim their identity in a new world marked by poverty and external dependence. Photo: von Puttkamer/National Geographic

REFERENCES

McIntyre, L. “Exploring South America.” 1990 New York: Potter.

Plotkin, M. “Medicine Quest.” 2000 New York: Viking.

McIntyre, L. “Last Days of Eden: Rondônia’s Urueu-Wau-Wau Indians.” National Geographic 1988 798-815.

Jacobs, JW, Petroski C, Friedman PA, Simpson E. “Characterization of the Anticoagulant Activities from a Brazilian Arrow Poison”. 1990 65(1): 31-35.

“Protection of Traditional Medicine: Is patent the whole problem or part of the solution?”, Cork Online Law Review, 2/25/2013

Detailed demographics of the Urueu-Wau-Wau