Three-toed Sloth Hanging Out ©kirkpatrickwildlife.com

Wild Perspectives from a Photographer’s Eye: Acclaimed wildlife photography and writing partners, Stephen and Marlo Kirkpatrick, share with Acaté their experiences of photographing and traveling the wilds of the Amazon Rainforest.

Their publications include the intimate and introspective photoessay Romancing the Rain: A Photographic Journey into the Heart of the Rainforest and Lost in the Amazon, the latter recounting a harrowing photographic expedition gone wrong in 1995 during which Stephen and four others got lost exploring a remote region of Peru. In this ordeal, the Matsés indigenous people, Acaté’s conservation partners, helped with their safe return to civilization, providing food and shelter.

Acaté recently had the chance to interview the accomplished husband-and-wife creative force, Stephen and Marlo Kirkpatrick. The photographic images we are fortunate to share with you are glimpses into the heart of the very region of the Amazon that Acaté is working to protect in partnership with the Matsés people. We are grateful to the Kirkpatricks for allowing us to share their perspectives and a few of their extraordinary portraits of Amazonia with you.

Stephen Kirkpatrick admiring the giant Ceiba tree of the Amazon rainforest ©kirkpatrickwildlife.com

Can you describe your first experience in the Amazon Rainforest? Did you have any preconceptions going in? Was the rainforest what you expected?

Stephen Kirkpatrick (SK): My first trip to the Amazon was in 1993. I’ve always been interested in photographing the “less explored” places where work is challenging and there are still opportunities to shoot places and subjects that have never before been photographed.

Treefrog (Osteocephalus planiceps) on Calladium , Amazonia ©kirkpatrickwildlife.com

My first trip to the Amazon was magical. I absolutely fell in love with the flora and fauna, and even with the heat and the rain. Shooting was a challenge as the subjects were so well hidden, but it was a challenge I welcomed. The pace there was slow – 12 hours of daylight, 12 hours of darkness – and that was a welcome relief from the hustle and bustle of my life in the United States.

I made 16 expeditions to the Amazon, and I have to confess that on some of the subsequent trips I didn’t find it so endearing, But on that first trip, it was love at first sight.

Confluence of Marañon & Ucayali, Amazon ©kirkpatrickwildlife.com

Marlo Kirkpatrick (MK): My reflection on my first trip there is a little more personal. I had been hired by Stephen Kirkpatrick to write a book called To Catch the Wind. Stephen had already completed the photography for that book, and while he was working with me, he was also traveling back and forth to the Peruvian Amazon working on the book that would become Romancing the Rain. At that point, Stephen was a client; there was nothing romantic between us. I wanted the contract to write the book on the Amazon, so I decided to go on an expedition with Stephen to see the rainforest for myself.

You have to understand something here – I had never before been camping, and I was about to head into the rainforest. Stephen tried to discourage me from going, largely because he was afraid he would be stuck babysitting me instead of working. It was a 10-day trip, and somewhere around day four, we realized we were in love. As I tell people now, if you fall in love in the Amazon, it’s real love. There was no electricity, the water we bathed in came right out of the river, and we were sweaty and covered with bug bites. Neither of us was looking our best, but the adventure we were sharing helped make it romantic.

A year later we returned to Peru and were married in an orchid garden at Machu Picchu. (At least we think we’re married; the ceremony was in Spanish and we have a paper in Spanish that seems to indicate we’re legally wed). So for me, my first trip to the Amazon will always make me think first of falling in love under a full moon shining through the canopy.

Amazon Yahuarachi School ©kirkpatrickwildlife.com

In what ways has your understanding or appreciation of the rainforest evolved over time?

SK: The most important lesson I learned was to respect the rainforest. My first expedition was magical; my second was disastrous. Poor planning and a hand drawn map left me and four others lost in the rainforest for almost two weeks. What started as a photo expedition turned into a life-threatening situation. Everything I found so enchanting the first time around – the rain, the animals, the crazy jungle soundscape – now seemed to be a sign of danger. The rainforest is hard on photographic equipment and it’s hard on physical human bodies. In the wrong situation, it’s even harder on your mental wellbeing.

At the end of that trip, I swore I’d never go back. I went on to return 14 more times, realizing I still loved the place. But never again did I underestimate its dangers or forget that it can be as deadly as it is beautiful.

MK: I never had an experience like Stephen’s that was life-threatening, but I did have some trips to the rainforest that were, shall we say, less than comfortable. I have to say, though, that the unpleasant trips made for better stories than the trips where everything went right.

The powerful red howler monkey (Alouatta seniculusis) is known to the Matsés as achu ©kirkpatrickwildlife.com

When admiring your breathtaking photographs of rainforest animals, people may not realize the effort involved in capturing such extraordinary glimpses of these elusive inhabitants. Can you share the challenges of photographing in the deep jungle?

SK: I could go into endless detail on that question, but I’ll try to keep it brief. The humidity and rain are murder on camera gear. Everything gets wet, no matter how great an effort you make to keep things dry. The camera lenses are constantly fogging, both inside and out. In the days when I shot film instead of digital, the moisture would cause the film emulsion to swell inside the camera, ruining the shots on the film and “gumming” up the inside of the camera itself.

The other issue is light. It’s hard to describe how dark it can be under the canopy to someone who hasn’t been there. It’s difficult to get a good shot of an animal when it’s so dark, or when that animal is high up in a tree and therefore silhouetted.

Tapir illuminated on the riverbank at night (Tapirus terrestris) ©kirkpatrickwildlife.com

Finally, many of your subjects – insects, poison dart frogs, snakes, and birds – are small and are often camouflaged. You have to keep your eyes open and practice constant diligence or you could walk right past a great opportunity and never know it’s there.

All that said, the challenges of shooting in the rainforest make getting a great shot or shots there all the more rewarding.

“[The Amazon is] a true circle of life. So many species are interdependent upon one another. Something people celebrate as “beautiful” might not exist if something “ugly” or unpleasant was not living there right beside it.” — Stephen Kirkpatrick

You have photographed a diverse array of Amazonian wildlife over the course of your travels. Are there any specific mammals or birds that you felt particularly fortunate to encounter and image?

All of them!

I do have some favorites. I literally dreamed about getting a shot of a brown-throated, three-toed sloth hanging in a tree high over the river, and a few days later, I captured that image. It required climbing on a guide’s shoulders while standing on top of a houseboat, but I got it.

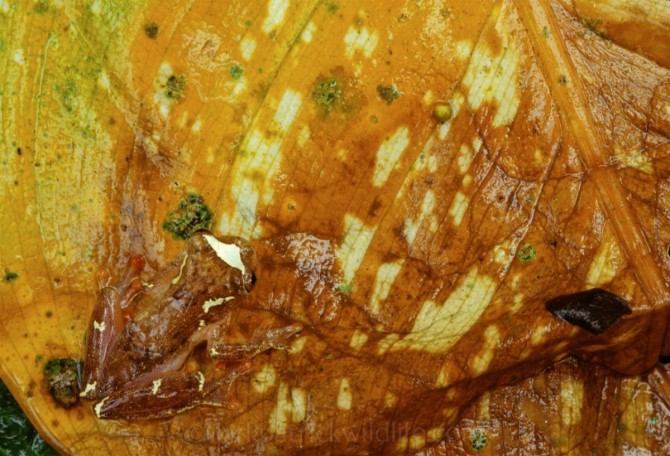

I also captured an image of an Amazon leaf frog (Cruziohyla craspedopus) that was at the time one of the first images of that particular species.

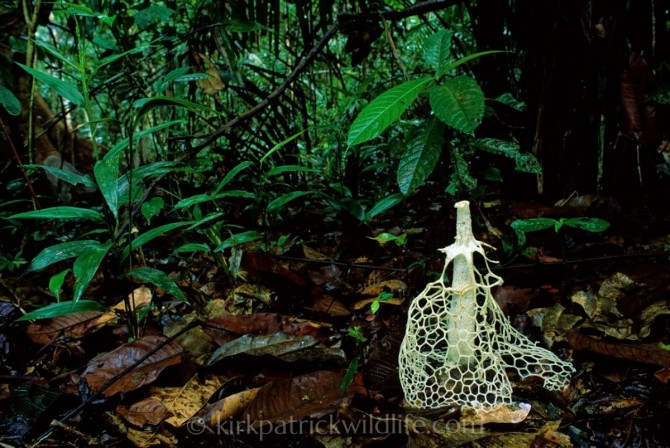

I found and photographed a veiled stinkhorn, a beautiful fungus, by smelling for it in the jungle; it blooms at night and has a pungent scent, but doesn’t live for more than a few hours. Sniffing it out and shooting it quickly is a must.

A Veiled Stinkhorn (Dictyophora indusiata) in the understory ©kirkpatrickwildlife.com

I love photographing snakes, and the Amazon was full of colorful specimens that I enjoyed shooting but that most people (including my native guides) get squeamish just looking at.

A gaping Black-skinned Parrot Snake (Leptophis ahaetulla nigromarginatus)©kirkpatrickwildlife.com

Cone-headed Katydid ©kirkpatrickwildlife.com

There are dozens of other shots that the average person might find ho-hum, but that are special to me because of the incredible time and effort it took to capture them.

Lightning on the Rio Momon, Peru ©kirkpatrickwildlife.com

Many species such as this Lettered Aracari (Pteroglossus inscriptus) depend upon hollows in old growth trees for nesting. Kirkpatrick set-up in the dark and waited for over 11 hours for 2 quick shutter-snaps of the bird as it poked its head out in the morning©kirkpatrickwildlife.com

One cannot help but notice the plants, trees and fungi that frame your wildlife pictures. What are your thoughts on the interaction between the fauna and flora of the Amazon Rainforest? How do you incorporate this in the composition of your photographs to capture the life of the rainforest?

SK: It’s a true circle of life. So many species are interdependent upon one another. Something people celebrate as “beautiful” might not exist if something “ugly” or unpleasant was not living there right beside it.

Leaf Mimic Katydid ©kirkpatrickwildlife.com

What is perhaps the single most remarkable or memorable moment from your time in the Amazon? Was it a photo? Was it an intangible realization?

SK: That’s a hard one. I fell in love with my wife there, so that’s definitely a high point. I was able to see and photograph plants and animals most people never see up close, including some that had rarely been seen by other humans. I also met some of the native people and experienced their way of life, which made me both grateful and a little repulsed by life in America, where we have so much and waste so much.

In Lost in the Amazon, you recount a harrowing photographic expedition in 1995 during which you and four others explored a remote region of Peru in the territory of the Matsés indigenous people, Acaté’s conservation partners. What led you to decide to explore that region and can you recount your experience?

SK: I was dreaming of shooting 12 National Geographic covers on that one trip! Seriously, the opportunity to shoot in a region that had never before been explored or photographed was incredibly intriguing.

Five of us were dropped off in a remote area by boat. The plan was to hike to a pick-up point in a village several days’ journey away, taking photos of everything we saw along the way. I was imagining all of the exotic images I’d capture and hoping I might even become the first to photograph some new species. Unfortunately, it didn’t work out that way.

Monkey Frog (Phyllomedusa vaillanti) ©kirkpatrickwildlife.com

The trip was a disaster from the first hour. The map we had was inaccurate, and the natives we hired at the drop off point to help carry our gear basically told us, “You can’t get there from here.” The whole expedition turned into the rainforest version of Ron Howard’s “Apollo 13.” The mission was no longer to take photographs, it was just to get out alive and find our way home.

We struggled with lack of food and water, injuries along the way, and our own fears and doubts. We had to spend every minute walking, trying to find our way out, so I had very little time to take photos. The images I did capture, along with most of our gear, ended up in the bottom of the river following a disastrous boat wreck that also left me with an injured leg. We eventually made it out, but it was quite the harrowing journey.

A basking Caiman Lizard (Dracaena guianensis), a species known to the Matsés as shutudun ©kirkpatrickwildlife.com

When lost in the deep jungle, were there marks of modern civilization or encroachment that were obvious to you?

SK: Not on that particular trip, and on that trip, they might have been a welcome sight.

One of the oddest things to me in all of my jungle journeys has been seeing the t-shirts the native people in these remote areas somehow end up wearing. They get them from missionaries or other explorers, and they all reference typically American themes. My wife is from Memphis, Tennessee, and she once saw a native in the depths of the jungle wearing a t-shirt promoting the Memphis in May Barbecue Festival from a decade earlier. My favorite was one I saw on a little guy in the absolute depths of the rainforest that said something like, “No waves, no girls, no fun.”

What were your experiences and impressions of the Matsés people? What surprised you most about their way of life and conception of the world?

SK: They were so kind to us, when they had no idea who we were or what in the world we were doing there. They shared their food and gave us shelter.

Giant River Otters (Pteronura brasiliensis) can reach lengths of up to 6 feet. Their boisterous dog-like barks are rarely heard in many areas of Amazonia due to local extirpation for the pelt-trade. ©kirkpatrickwildlife.com

Looking like it got flattened by a tire, the Suriname Toad (Pipa pipa) is a remarkable amphibian. The tadpoles develop protected in pockets in the mother’s back and emerge as fully formed toadlets ©kirkpatrickwildlife.com

After surviving your harrowing ordeal and returning to the United States, how did the distance and reflection affect your perception of the Amazon?

SK: Respect. There are many opportunities to see and experience the Amazon as a casual tourist or as a more serious explorer, and I encourage people to do that. But I also warn people that it’s not a place you should go off into half-cocked without realizing its sheer natural power and its danger.

In the Amazon, beauty and danger are inextricable. Tarantula (Theraphosidae sp.) ©kirkpatrickwildlife.com

What are the most pressing issues that you would like the world to know about from your experiences in the Amazon Rainforest?

SK: It is a place of beauty worth seeing and preserving, but to truly understand it, you can’t simply read about it in a textbook. To truly understand and really know the Amazon, I think you must experience it first hand.

From your writings, it is clear that your Christian faith is a major compass and guiding force in your lives. Do you think organized religion, in general, can be a call to action for the conservation effort?

SK: I think we are called to be stewards of this planet God created, and that wise people understand that we should respect and care for the flora and fauna of the world as God’s creations. On the flip side, I also sometimes see a tendency in people to worship the creation rather than its Creator. In my own experience and my own belief, the beauty and intricacy of nature is a signpost pointing to the Creator.

Do you have any artistic inspirations that have influenced the direction or style of your photography?

SK: The Hudson River School of painters has been a creative influence. I find inspiration in creativity in many art forms, including music as well as the visual arts.

Rufescent tiger heron (Tigrisoma lineatum), a familiar sight prowling along the riverbank ©kirkpatrickwildlife.com

What is your next major assignment?

SK: I’m currently working on a book on waterfowl, primarily ducks in flight. I also enjoy underwater photography, which has taken me to the Caribbean for recent projects. Marlo and I were able to swim with and photograph whale sharks this spring in Utila, Honduras, and hope to return there for future projects.

The rare and spectacular Amazon Leaf Frog (Cruziohyla craspedopus) on a Heliconia ©kirkpatrickwildlife.com

About Stephen and Marlo Kirkpatrick

Stephen and Marlo marrying at Macchu Pichu in 1998 ©kirkpatrickwildlife.com

Stephen Kirkpatrick

Wildlife and Nature Photographer

Stephen Kirkpatrick has been chased by grizzly bears, attacked by alligators, and nibbled by piranha. In the process, he’s captured some of the world’s most beautiful and exciting nature and wildlife photography.

Kirkpatrick’s appreciation of nature began in childhood, when he divided his time between caring for a menagerie of unusual “pets” and operating a snake farm in his parents’ backyard (admission 50¢). His fascination with nature became a full time career when his father gave Kirkpatrick his first camera in 1981.

Since then, Kirkpatrick has published more than 3,500 photographs in books and magazines worldwide, including Delta Sky, Skin Diver, Audubon, Gray’s Sporting Journal, Natural History, Ducks Unlimited, Outdoor Photographer, BBC Wildlife, National Wildlife, Sports Afield, and others.

Kirkpatrick has published 11 solo pictorial coffee table books. His latest, Sanctuary: Mississippi’s Coastal Plain, is a tribute to the rare and endangered species and habitats of the Mississippi Coastal Plain. Kirkpatrick’s other titles include Among the Animals: Mississippi, Images of Madison County, Mississippi Impressions, Lost in the Amazon, Romancing the Rain, Wilder Mississippi, To Catch the Wind, In Wilderness Song, Wild Mississippi, Whistling Wings, and First Impressions. His last eight books were written by Kirkpatrick’s wife, author Marlo Carter Kirkpatrick.

Kirkpatrick’s work has earned international acclaim, including the Writer’s Digest International Self-Published Book Award, the National Outdoor Book Award, the Benjamin Franklin Award, and three Southeastern Outdoor Press Association Book of the Year Awards. He has twice been named a winner in the prestigious International Wildlife Photographer of the Year competition held in London, England.

Kirkpatrick is in demand as a featured speaker for national conferences and conventions. He has appeared on multiple network televisions shows including ABC’s “Shark Tank,” the Christian Broadcasting Network’s “The 700 Club,” The Outdoor Channel’s “Adventure Bound Outdoors,” and “Wild Things” and on several PBS and outdoor network specials.

Marlo Carter Kirkpatrick

Freelance Writer/Author

Author Marlo Carter Kirkpatrick lives in Madison, Mississippi, with her husband, professional wildlife photographer Stephen Kirkpatrick.

Marlo is the author of Lost in the Amazon: The True Story of Five Men and their Desperate Battle for Survival, Mississippi Off the Beaten Path, a guide to unique attractions currently in its seventh edition; and It Happened in Mississippi. She and her husband collaborated on the children’s book Among the Animals and on the coffee table books Sanctuary: Mississippi’s Coastal Plain, Images of Madison County, Mississippi Impressions, Romancing the Rain, Wilder Mississippi, and To Catch the Wind.

Marlo’s work has taken her to destinations throughout North, Central, and South America, as well as Africa and the Middle East. She has won more than 200 local, regional, and national awards for creative excellence, including the National Outdoor Book Award, the International Self-Published Book Award, the Benjamin Franklin Publishing Award, and three Southeastern Outdoor Press Association Book of the Year Awards.

Marlo and Stephen fell in love on an expedition to the jungles of the Peruvian Amazon, and returned to Peru in 1998 for their wedding ceremony at Machu Picchu. The Kirkpatricks have since made several return trips to the rainforest. On a recent expedition, Marlo complained of snakes under her bed and cockroaches on her toothbrush. Stephen told her she was “just too high maintenance.”

Marlo is a cum laude graduate of the University of Mississippi with degrees in journalism and English. Prior to launching her freelance career in 1995, she was senior writer with an advertising agency. Active in animal welfare causes, Marlo was a founding board member of the Madison Ark animal shelter. She and Stephen are frequently accompanied on their travels by their dogs, Blizzard, Snowflake, Batman, and Joker.

Kirkpatrick Wildlife: Prints, Photography Trips, Workshops, and more!

A jungle still: Tiger-striped Leaf Frog (Phyllomedusa tomopterna) in the Peruvian rainforest ©kirkpatrickwildlife.com