View of fish pond on Matsés land with small farm on hillside.

Nothing is more challenging than advising experts.

The Matsés indigenous people are master farmers, and it seems strange to even suggest farming ideas to people who live almost entirely off the land. The problem is that their traditional small-scale swidden (slash-and-burn) approaches to farming, once superbly adapted sustainable agriculture for a semi-nomadic lifestyle, do not translate to newer, larger fixed settlements.

Prior to sustained outside contact, the Matsés lived in small villages scattered over a vast expanse of rainforest. Game and fish were easily accessed and in abundant supply, and agricultural fields were developed through traditional slash-and-burn methods which released nutrients into the soil providing adequate yields for two or three years. Research shows that this approach to farming is more efficient for smaller populations of semi-nomadic peoples than more elaborate or organized methods of agriculture.

After two or three years, the nutrients get washed away by the heavy rains and the soils are depleted. At that point of low yield, the Matsés would simply relocate their village to another area, allowing the jungle to once again reclaim the land.

Recent Agricultural Methods of the Matsés

Following contact, the Matsés reorganized into larger, fixed super-nucleated villages along the rivers at the encouragement of missionaries to facilitate assimilation into modern culture and access to trade goods. This new permanence of settlement, coupled with the old practice of slash-and-burn agriculture, has led to rings of increasing disturbed forest around each community. Once the soil gets exhausted in a few short years after a burn, the Matsés have no alternative but to cut virgin rainforest to create new farms each year, edging their fields farther and farther away from their fixed settlements. This creates a significant burden for the families carrying heavy loads of bananas and sacks of cassava (Manihot esculenta) for as long as two-hours to return back home. It also makes for longer walks for the men on hunting trips.

Location of Estirón, Perú near the Perú-Brazilian border ©Google

Ever increasing farm plots expanding from Estirón as the Matsés continue slash-and-burn agricultural practices

The relevance of their environmental impact extends beyond their community. Agriculture is a major driver of tropical deforestation and greenhouse gas emissions. While small farmers have less impact compared to industrial soy, sugar cane, and cattle production, the localized effects on biodiversity can be profound.

Sustainable Agriculture in the Amazon

To provide a proven alternative, Acaté Amazon Conservation has started a permaculture farm in the village of Estirón where our field coordinator, Dr. David Fleck, lives. Building and integrating regenerative systems into the Matsés agricultural practices will not only benefit them with higher yields and more nutritious food, but will also curtail rainforest deforestation, because the land will be able to continuously produce food rather than be depleted and abandoned. It is model that can be scaled with proper design, and applied to other threatened areas of the Amazon.

Permaculture is a holistic systems approach for, “consciously designed landscapes which mimic the patterns and relationships found in nature, while yielding an abundance of food, fiber and energy (shelter, medicine) for provision of local needs.”* The challenge in any newly introduced framework like permaculture is how it is adapted and integrates with the current cultural practices of the people using it.

Acaté permaculture experimental Matsés farm in Estirón, Chobayacu, Perú

One could make the argument the what we now call permaculture is comparable to truly traditional pre-contact Amazonian farming culture.

Increasing evidence is emerging that indicates that pre-Columbian Amazonian communities nourished much larger populations than previously thought possible in lowland Amazonian rainforest.

Archaeologists have been encountering terra preta do índio (dark earth) soils in many areas of Amazonia; exactly how these earlier indigenous peoples were able to enrich the soil remains unknown to science. Surveys have even found what appears to be farming swales and circles.

This extensive and robust agricultural knowledge was lost during the holocaust that followed European disease and conquest. It is difficult to imagine the extent of devastation; indigenous populations in the Americas is estimated to have declined 95% from a peak of 10-million inhabitants.

Implementing Permaculture Practices in Estirón

A culturally-inclusive Matsés permaculture design calls for working in already cleared areas next to the villages, what is referred to as Zone 1. By utilizing various infiltration basins to collect mulch, water, and nutrients, food staples like plantains (starchy bananas) and cassava are able to be produced close to home without depleting the soil of its nutrients.

Banana/Plantain & Papaya Circles

The banana circles/basins are placed closest to the homes to allow for the easy addition of kitchen waste and ashes into the center of the circles, which slowly release nutrients to the growing bananas. This also permits the chickens, which are kept near the houses for protection, to add valuable guano in the process.

Normally, banana circles include thick ground cover plants to protect the soil from weathering and control weeds. In the Matsés territory, however, there are so many jergóns (Bothrops atrox), a deadly pit viper, we are only using sparse ground cover and mulch to avoid giving them hiding places.

Usually covered with mulch, the Matsés fear creating pit viper habitat by mulching many of the banana circles.

A banana circle further away from the Matsés homes where mulch is piled on thicker.

Contour Swales

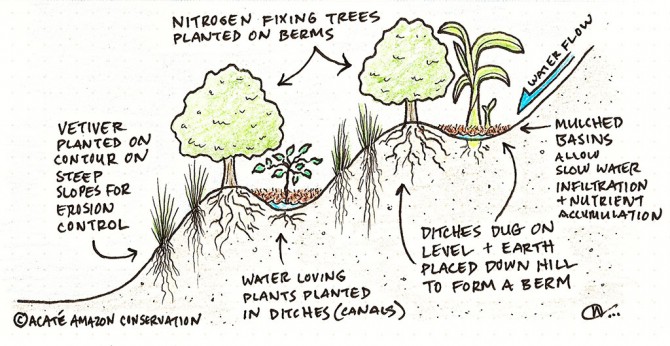

Cross section of sloping hillside showing contour rwo-croping basins (swales) and plantings

For the contour row cropping system, we selected a hilly area near the village and are utilizing two nitrogen-fixing tree species: guaba (Inga edulis) and amasisa (Erythrina poeppigiana).

Guaba and amasisa both respond well to heavy pruning which provides much needed mulch for soil protection, weed control, and releases nitrogen into the soil when cut back. By planting on contour (i.e. planting in a level line perpendicular to the slope of the hillside) we reduce erosion by slowing water’s path down the hill. When water is slowed, its kinetic energy is reduced and more soil stays on the hillside rather than running downhill, collecting at the bottom.

In the areas between the rows we have planted a polyculture of staples like cassava, peanuts, peppers, sweet potatoes and cocona (Solanum sessiliflorum). In the steeper areas, to control erosion and hold valuable nutrients, we are adding vetiver (Chrysopogon zizanioides) swales and rotting logs. The vetiver grows in such tight clumps that it actually arrests the flow of water,and its deep root system—up to six-feet tall—holds the soil in place. The decaying logs helps build fungal networks essential to proper plant nutrition and soil creation.

To help with the bane of tropical agriculture, leaf cutter ants (curuincis), we are using hierba luisa (lemon grass) barriers around young plants. For the protection of important fruit trees and the young guabas we are using special leaf baskets around the saplings to deter leaf cutter ants and wooly rats.

Leaf baskets protecting baby guaba saplings

Moat to limit access by leaf-cutter ants

Partnership and Community Initiative

Acaté’s agricultural assistance is only initiated from the requests and needs of the Matsés themselves. We have been careful to avoid the type of top-down approach in conservation initiatives that has repeatedly failed time and time again. At Acaté, we realize that you cannot lead from the rear. So, instead of offering classes and talking about permaculture, we putting our advice into practice, learning and adapting strategies in real time with them!

The Matsés are a proud and highly competitive people. When the new systems yield big bunches of bananas and high crop yields, we anticipate they will be copied widely and spontaneously throughout the rest of the community.

In addition to agricultural practices, Acaté looks forward to implementing many more regenerative and sustainable design approaches and practices to help the Matsés achieve a comfortable level of self-reliance. We also look forward to learning from the innovations that the Matsés farmers will generate on their own as they integrate permaculture into their lives!

View of current Matsés farm in Estirón, Chobayacu, Perú