Mature siante tapun plant with author's son for scale ©Acaté

Preserving Matsés Agricultural Heritage

The Matsés people of the Amazon are master farmers. Worldwide, inestimable indigenous agricultural knowledge has been lost in the process of acculturation. Forgotten often before it is realized what has been lost, the insidious erosion of traditional farming is a well paved path leading to weakened resiliency, increased dependence on outside manufactured foods, and greater draw into the cash economy driving unsustainable economic activities. Tragically in many indigenous groups, loss of traditional diets has contributed to malnutrition and diabetes. Acaté’s innovative program with the Matsés aims to halt this real-time decline, thereby protecting the Matsés’ rich agricultural legacy for future generations. In our latest report, Acaté field coordinator Dave Fleck presents his fascinating work with the Matsés to save indigenous ‘heirloom’ jungle crops to maintain nutritional and genetic diversity of their farms.

The Matsés practice high diversity perennial intercropping polyculture agriculture. In plain terms, on the same piece of land they plant many types of crops that produce over several years, as opposed to annual monoculture, where a single crop is planted and harvested each year. Polyculture systems like that of the Matsés have many advantages. They provide a diversity of foods with different nutritional properties, which make them ideal for subsistence purposes. They are practical in that if one crop fails, there will be multiple other crops still available. Additionally, some crops provide shade and/or ground cover, reducing erosion and creating favorable microclimates for other crops. Some pairs or groups of crops complement rather than compete with each other for nutrients.

The polyculture techniques used by the Matsés and other indigenous Amazonians originated thousands of years ago and have incorporated successfully Old World crops (such as plantains, bananas, papayas, etc.) during the last 500 years. Indeed, there is much to be learned from indigenous agricultural practices, so it is a tragic loss to all as the Matsés’ swiddens become less diverse, as tends to follow increased assimilation to Western culture.

Matsés polyculture swidden, showing in this shot manioc, plantains, and papayas ©Acaté

The principal crops in the Matsés’ polycropping system are manioc and plantains (both having multiple cultivated varieties), which are always planted together in their swiddens and comprise their principal, year-round staple foods. A third important crop is maize, which is traditionally planted interspersed with the manioc and plantains. (Today some Matsés are starting to plant maize as a monoculture in separate swiddens.) In addition to these staple crops, the Matsés plant many secondary food crops in smaller proportions interspersed with the manioc and plantains, including several types of sweet bananas, papaya, sugar cane, pineapple, sweet potato, and cush-cush yams (a climbing vine with potato-like tubers; see the table in Appendix 2 for a list of all the Matsés crops).

Of current interest to Acaté are four closely-related plants in the Araceae family. They are all taro-like plants with large “elephant ear” or “arrowhead” type leaves and edible corms. (a corm is reminiscent of a root or tuber, but technically it is a bulb-like underground stem). The corms of these plants are of varying sizes, shapes, and tastes and are all boiled and eaten by the Matsés. The flowers and fruits are produced seasonally during the dry season (June to August), and as we have only recently taken interest in these plants we have not been able to examine the fruits and flowers carefully yet, so we have not been able to identify these plants to scientific species with certainty yet. Nevertheless, it is certain that they are in the Araceae family and evidently in the genera Xanthosoma or Colocasia, or in closely related genera. All four of these plants are in the process of being lost from Matsés swidden agriculture.

Description of the four endangered Matsés crops

Adult bëbiukud plant ©Acaté

1. Bëbiukud is the Matsés name for a plant that is probably Xanthosoma sagittifolium. However, since this genus is native to South America, has several cultivated species, and there are many wild species in Matsés territory, we cannot be certain until flowers are collected. The Matsés name literally means “one that peels by itself”, in reference to the observation the (inedible) papery skin of the corm peels away on its own when boiled. The leaves are arrowhead-shaped, and some of the larger leaves have basal lobes that are as long as the leaf blade. Leaves are up to 52cm long (measuring from the apex of a basal lobe to the apex of the blade). The leaves have a submarginal collecting vein (i.e., a vein that goes around the perimeter or the leaf a few millimeters from the outside margin of the leaf). As with all four plants of interest, the leaf petioles grow directly from the top of the corm, so there is no stem other than the underground corm. The main corms are the size of a fist, somewhat flat, orangeish on the inside, and have a mildly sweet taste. Growing around the basal corm are many spherical edible cormels (small corms growing from the side of the main corm) 2-3 cm in diameters. The Matsés report that the skin of the corm can produce a slight rash if handled excessively.

Young siante tapun plant ©Acaté

Adult siante tapun plant with author’s son for scale ©Acaté

2. Siante tapun is much larger than bëbiukud, but the two can easily be confused when the siante tapun plant is immature. It is possibly also in the genus Xanthosoma. It has few but huge leaves (up to 120 cm long) with well-developed basal lobes. The basal lobes of the larger leaves are a bit over two-thirds the length of the blade. The leaves have submarginal collecting veins. The petioles are thick and up to cm 125 cm long. As with the other plants of interest, the leaf veins are reticulate (i.e., in the form of a net) and ribbed (i.e., jut out prominently on the underside); but distinctively for siante tapun, the veins, including the tiny veins, produce sharp grooves on the top of the leaf that can be seen clearly when the sun shines upon the leaf at an angle. The other plants have smooth grooves and only where the main veins are. Siante tapun does not have a large central corm; rather, the first corm is shaped like a club and grows to one side, and similarly-shaped cormels radiate out from its constricted base, such that in an adult plant it is hard to know which is the corm and which are the cormels. The corms and cormels are about 15 cm long and 5 cm wide, with red tips and buds. The “meat” of the boiled corm has a soft texture, and tastes like a potato. The name siante tapun literally means “spear root” (in reference to the spear/arrow-shaped leaf). A synonymous name for this plant is opa shui “dog penis”, alluding to the red-tipped and elongated characteristics of the corms. It is also called tëdi tapun, the term tëdi being another name for “spear.”

Camis corm and cormels ©Acaté

Cluster of adult camis plants ©Acaté

Red petiole tips of the camis plant ©Acaté

3. Camis seems to be the common taro plant, Colocasia escuelenta. The term camis has no analyzable meaning and has cognates in other Panoan languages, suggesting that it is a very old term. Since C. escuelenta is native to southern Asia and the genus Colocasia is not native to the Americas, it must have been introduced after European contact. However, it would have been introduced more than 100 years ago, before the Matsés had contact with non-Indians, possibly through contact with other indigenous groups. Since I am not certain of its identification, it is also possible that it belongs to a different, local genus of Araceae. Camis is readily distinguished from bëbiukud and siante tapun. It has medium-sized leaves (up to 46 cm long) with basal lobes that are joined to each other below the point where the petiole is attached, giving the leaves a more roundish than arrowhead-shaped appearance. The leaves lack submarginal collecting veins. The top surface of the leaves are fairly flat and smooth, and repel water as if they were coated with oil. The leaf petiole is thin, relatively long (up to 96 cm) and distinctively dark red where it connects to the leaf. The camis plant has the largest corm of all, the size and shape of a coconut, with multiple curved tear-shaped edible cormels surrounding it. Unlike the other three plants described here, the corm in mature camis plants grows at least halfway out the ground. As the cormels grow, they remain attached to the main corm and quickly produce their own leaves, such that by they time they are one year old they have formed a cluster, like the one seen in the photograph. The “meat” of the corm is white and has an almond-like flavor. Two varieties of camis were known to the Matsés: a white variety, which is described here, and a red variety that seems to be completely lost since at least three decades.

Made mapi corm ©Acaté

4. Made mapi literally means “paca head” (a paca is a dog-sized rodent). It is the smallest of the four plants. Its corm is roundish or oval and the size of a softball, presumably reminiscent of the size and shape of the head of a paca. A more detailed description is of this plant is pending as I have only very recently had some corms sent to me. They Matsés say that the leaves are similar to those of the camis plant.

Advantageous characteristics of these plants

All four plants have several properties that make them of interest to agriculture. First, they are all extremely hearty plants: if they are not completely destroyed when the corms are harvested, any corms or cormels that remain in the ground will sprout new leaves. Even after a swidden is abandoned, the plants continue to live, though somewhat underdeveloped, presumably due to the lack of sunlight and competition with successional plants. After 15- to 20-year-old secondary forest from an abandoned swidden is cut down and burned, it is common for these plants to grow up into large heathy specimens from the old corms. In fact, many of the plants that I have obtained were found in cleared secondary forest. Most other Matsés crops do well only when the soil is enriched by the abundant ashes produced by burning the felled trees of a new swidden, but the four aroid plants of interest here persist even after the ashes and thin topsoil have eroded away.

Another advantage is resistance to pest damage. Unlike manioc, their leaves are not sought after by leaf-cutter ants. They also seem to be resistant to all other insect damage: (unlike plantains) they are not infested by corm-boring beetle larvae (grubs), and their leaves are free of damage by caterpillars. These crops add variety to the diet, and corms of Xanthosoma and Colocasia are known to contain protein. Furthermore, they provide ground cover for other plants in Matsés polyculture swiddens. In addition to these advantageous properties, they are part of the Matsés’ cultural heritage. Their only drawback is that the corms are most agreeable when the leaves wilt seasonally, so they usually harvested only during the dry season.

Loss of Matsés crop diversity

While all four of these aroid crops were formerly planted in all Matsés swiddens, today very few Matsés still plant them, and currently no Matsés farm (other than mine) has all four. In fact, the made mapi plant took me many months to eventually locate and acquire from the remote Matsés village of Puerto Callao, apparently the only place where it can still found. It is the very old women who still have interest in these plants and who still plant them in swiddens (and who kindly provide me with corms to propagate them). Of the four plants, the one most commonly still planted is bëbiukud. The other three are in serious danger of being lost, not just to the Matsés, but also to Western science. While some of these Matsés crops may be common, it is possible that some are genetically unique cultivars or even new crop species.

Conservation strategies

The goal of Acaté Amazon Conservation with respect to these plants is to identify and sustain them in cultivation. Over the past year I have been collecting these plants and growing them next to my house and in my swidden at the Matsés village of Estirón where I live. We plan to propagate them and promote their planting by encouraging the Matsés to incorporate them into the permaculture plots that they would establish as part of a planned project sponsored by Acaté Amazon Conservation. These permaculture plots will be set up in cleared secondary forest adjacent to Matsés homes, where polycropping and soil restoration techniques will be used so the Matsés can provide themselves with supplementary food. We have already begun to experiment with some permaculture plot designs and techniques at the Matsés village of Estirón, as described in our June 2015 and November 2015 field reports]. I recently planted all four of the these plants in one of the experimental permaculture plots, to propagate them and to make sure that they do well in experimental plot before carrying out the project in other Matsés villages. We have high hopes for the success of these plants in permaculture designs, given their longevity, vitality in nutrient-poor soil, resistance to pests, utility as ground cover, and protein content. We are now seeking funding to set up permaculture plots for multiple Matsés families in all 14 of the Matsés villages in Peru.

Thanks in advance to any of our readers who wish to share with us their opinions or expertise with respect to these or similar plants.

Appendix 1: Update on the mystery plantain root-boring beetle

In the November 2015 field report, I provided information (and photos) of a plantain-corm-boring beetle larva that is a devastating pest in Matsés swiddens and our permaculture experiments. In that report I mentioned that the beetle grub that infests Matsés plantains was much larger than the larva of Cosmopolites sordidus (common name: banana weevil, banana root borer or banana weevil borer), the common worldwide beetle pest of plantains and bananas. I expressed my suspicion that it was a different species, despite not having seen the adult beetle yet. But now I have! Below is pair of photographs of two adult beetles that I found inside plantain corms that had been burrowed into by the larvae. The Matsés plantain beetle, in addition to being twice as large (25 mm in length) as an adult C. sodidus (12 mm), is not even a weevil, but rather appears to be a scarab beetle. I am writing this at the Matsés village of Estirón, where I do not have access to a library or the internet. Once I travel to a city, I will begin to try to identify the beetle; in the meantime, if any of our readers can help with the identification, it would be greatly appreciated.

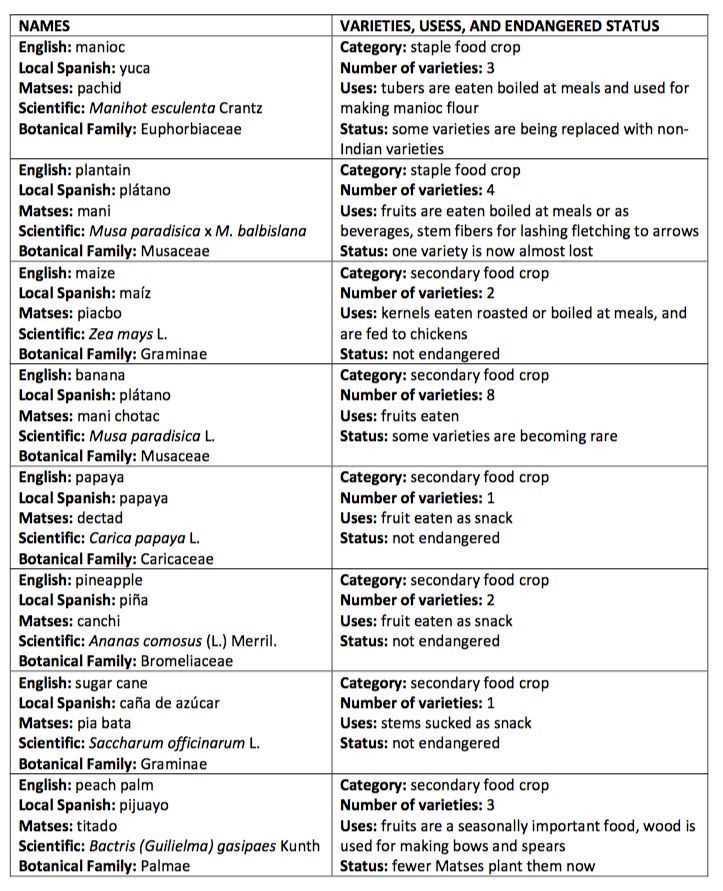

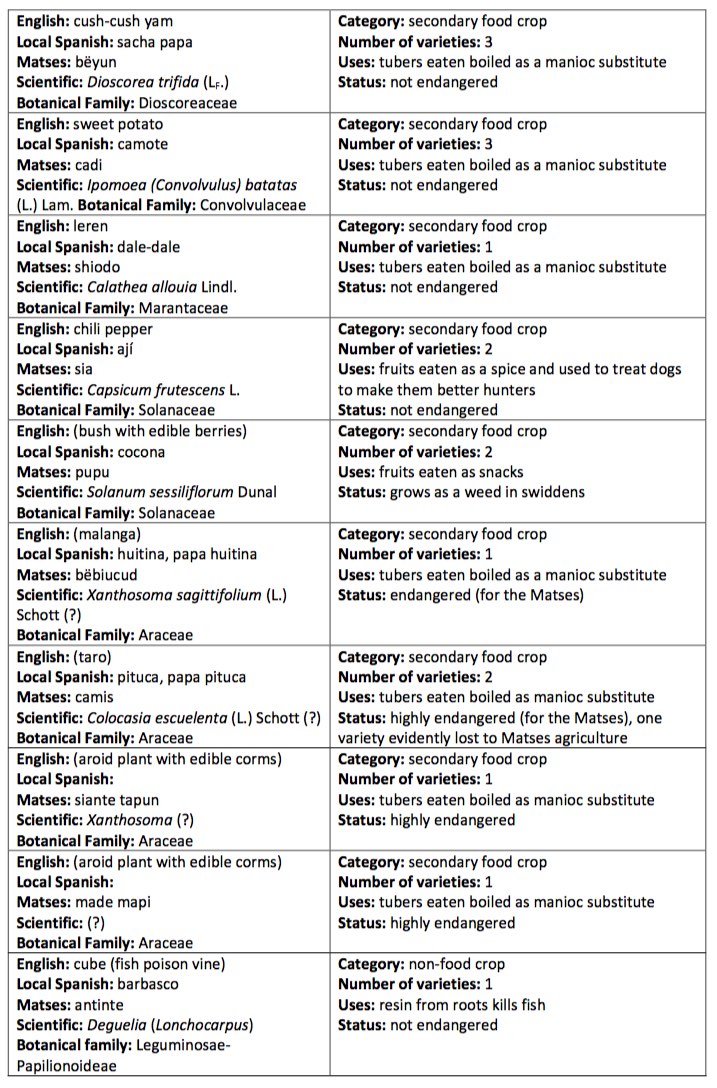

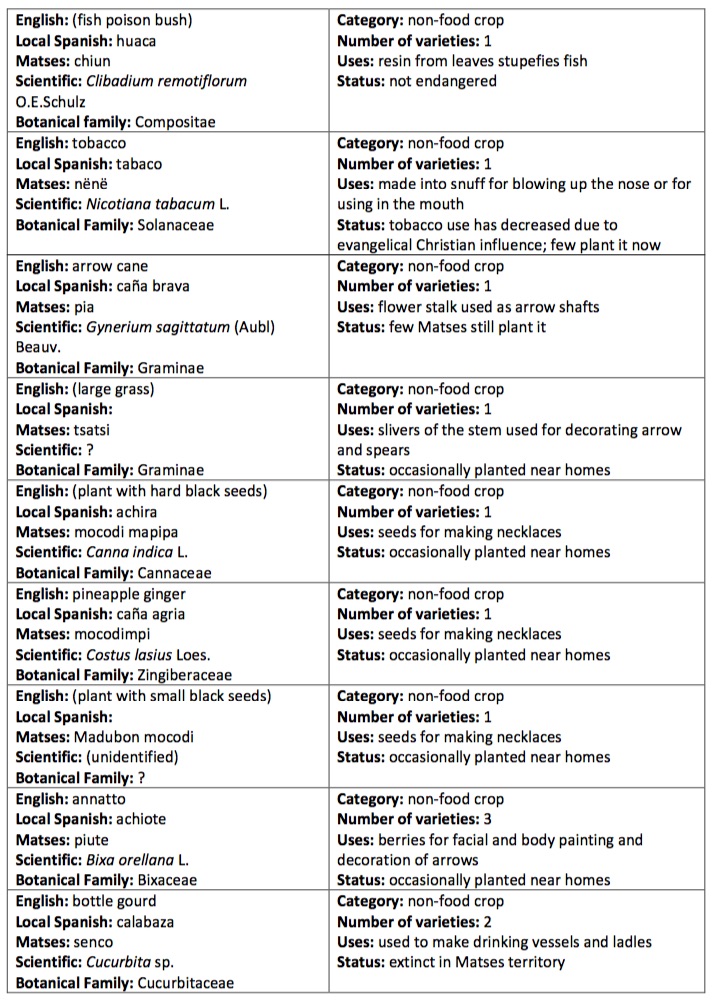

Appendix 2: Inventory of Matsés Crops and Conservation Status

The following is a list of the crops that the Matses currently plant or formerly planted in their swiddens, divided into three categories: 1) staple crops, 2) secondary food crops, 3) non-food crops. Within each category plants are arranged with the currently more numerously planted crops first. Note that many of the non-food crops are no longer planted in swiddens but are still planted near their homes. In addition to the crops listed here, the Matses plant many types of fruit trees near their homes. For each crop, the conservation status is assessed by Acaté based on trends and current presence in Matsés farms.